This is a good time to talk about Ulysses S. Grant. As president of the United States and commanding general of the Union Army before that, Grant fought for freedom and equality and the end of slavery, giving it his all.

That is why it was hard to understand, really jarring, when a bust of Grant was toppled in San Francisco by protesters who are part of the current nationwide struggle to end racism. But Grant likely would have understood. He knew better than anyone that unjust things sometimes happen in any great battle for justice.

Predictably, some commentators seized on the toppling of Grant’s statue to discredit the whole message of the protesters. Others suggested that it might have been because Grant was not a zealous abolitionist before the Civil War and that he seemed ambivalent toward slavery even at the start. Both are wrong.

It is true that Grant was not born enlightened. He came to enlightenment over time and, in the end, his opposition to slavery was unshakable and driven by passionate religious and democratic fervor. When it mattered most, he was a fierce warrior for equality for all.

As he said in his memoirs, finished just before his death, the South “was burdened with an institution abhorrent to all civilized people not brought up under it, and one which degraded labor, kept it in ignorance, and enervated the governing class.”

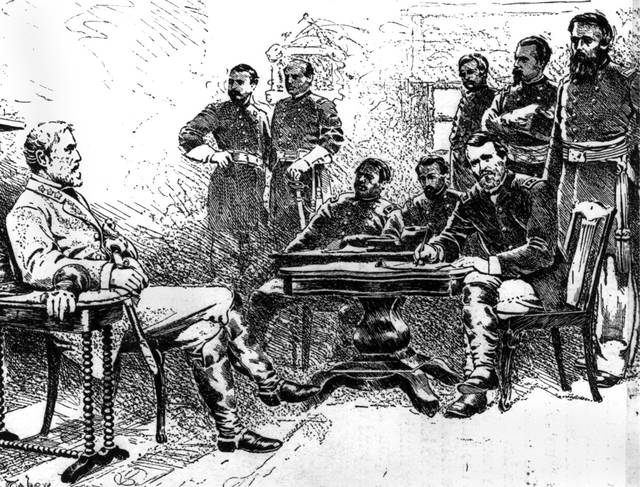

And Grant was more than words. President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, but Grant actually freed the slaves by constantly pursuing the enemy and crushing the will of the South. And, when he saw that former slaves needed to fight for their own freedom, he supported their enlistment in the Union Army.

As president, Grant successfully fought for passage of the 15th Amendment, guaranteeing Black Americans the right to vote.

And when white Southerners started acting like they had not lost the war, Grant demanded emergency powers to restore order and stop the anarchy and lynchings. Grant knew that white supremacists were nothing but terrorists, and the federal troops that he sent into the South arrested 3,000 Klansmen and restored order.

As historian Joan Waugh wrote in “U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth,” “In 1860, 4 million people were enslaved. But by 1863, emancipation had occurred, and by 1870 all male former slaves had the vote. Grant oversaw a social revolution that was unprecedented.”

And he wanted to do more. In his second term, when white Southerners began to use official measures and renewed violence to oppress Black citizens, Grant knew that he had to crush the haters with overwhelming force, just as surely as he had crushed the Confederate army and its treasonous generals.

But the compromises of 1876 effectively ended Grant’s reconstruction and the possibility of enforcing the rights of the recently freed slaves. If we had listened to Grant then, the promise of the Civil War would have been kept, Reconstruction would have completed its job and America would have been spared 150 years of systemic injustice and strife.

And it is likely that no one would need to march in our streets for racial justice.