WASHINGTON — In 1999, a rank-and-file Republican senator named Mitch McConnell was, in his words, the “go-to guy” for explaining how arcane Senate rules could influence the outcome of Democratic President Bill Clinton’s impeachment trial.

“The reason Clinton was not removed from office,” McConnell mused in his 2016 memoir, “was that Democrats were able to keep public opinion on their side, framing the impeachment trial as a partisan exercise and arguing the popular view that political investigations are nothing more than politics.”

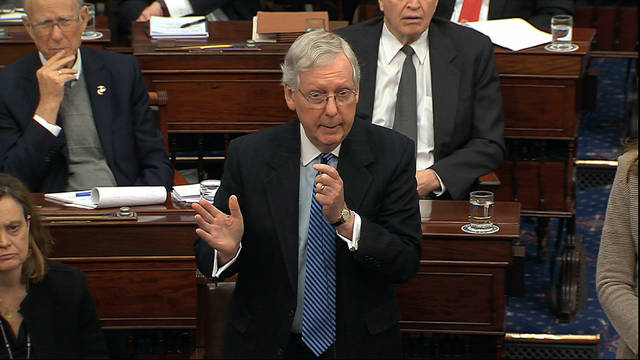

Twenty-one years later, as the Senate majority leader, McConnell is now at the center of another impeachment trial and is using a similar playbook to control the process and shape the narrative to protect his own party’s standard bearer, President Trump.

For months, the Kentucky Republican has been quietly preparing for the possibility of this impeachment trial, only the third in American history.

He has been educating GOP senators, coordinating with the White House, preaching the importance of party unity and bearing the brunt of Democratic attacks on behalf of his 53 members — some of whom are in close reelection races.

He has sought to undermine the impeachment inquiry launched by House Democrats by using daily floor speeches to demonstrate how the party should talk about the other chamber’s “impeachment obsession.”

Groundwork laid

But while McConnell could never have anticipated that he would be the top Senate Republican during a presidential impeachment, in many ways the 77-year-old has been preparing for decades to lead Republicans through a politically perilous moment like this one.

He grew up wanting to be a United States senator, and on the heels of winning his first Senate race in 1984 decided his dream job was to run the entire legislative body.

“He’s the only person at this point in the Senate that can manage the task at hand,” said Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C.

McConnell’s supporters are watching now with great excitement. They expect the events of the coming days to mark the triumphant culmination of McConnell’s years of study, observation and application of consensus-building strategies that have allowed him, time and again, to persuade colleagues to do what he wants while making them feel good about it.

“You have your destination in mind, you have your path to get there and, most importantly, you have to convince everybody else that they want to get there, too,” said Steven Law, a former McConnell chief of staff who now runs the super PAC aligned with the majority leader. “He has the strategy, he works that strategy, and most importantly he brings others along.”

Scott Jennings, a veteran of McConnell’s political campaigns and a longtime friend, predicted McConnell’s handling of the impeachment trial will energize his Kentucky base in a reelection year against a well-funded Democratic challenger.

“Have you been to Kentucky lately? They can’t get enough of Trump,” said Jennings, who recalled the enthusiastic welcome McConnell got at a local fish restaurant in Louisville after the Senate confirmed Trump’s controversial Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh in 2018.

But McConnell’s challenges are far from over.

Defections possible

McConnell had a victory earlier this week when he persuaded every Senate Republican to support the ground rules for an impeachment trial that would not allow a vote on witness testimony until the eleventh hour — a standard he said was in keeping with the rules for Clinton’s trial.

But he also agreed to make some concessions to the rules framework, which Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer suggested was a sign that McConnell’s hold over his party was starting to crack.

“The American people realized how unfair Leader McConnell’s resolution is, and they are telling Republican senators to change it,” Schumer, D-N.Y., crowed to reporters.

McConnell’s next obstacle will be to convince his members they don’t need to hear from witnesses later in the trial. He knows that legal fights over executive privilege could extend the proceedings indefinitely and witness testimony could potentially produce information damaging to the president.

It was unclear, however, whether McConnell will be able to control defections from moderate Republicans and vulnerable incumbents who may side with Democrats and insist on voting to subpoena witnesses.

Shaping history

And while McConnell has long held the reputation of being a fierce institutionalist, critics are pledging to make sure the majority leader goes down in history not as a savvy rules tactician, but as a ruthless political operator who loves his party more than he loves the Senate.

Democrats point to how McConnell refused in 2016 to hold confirmation hearings for outgoing President Barack Obama’s pick to join the Supreme Court, then changed the Senate rules in 2017 to ram through Trump’s nominee.

McConnell’s most recent posturing around impeachment — setting party-line parameters for the impeachment trial and boasting on Fox News about his “total coordination” with Trump’s legal team — has reignited complaints.

“He, who has characterized himself as a man of the Senate, has given his life to this institution, is destroying it brick by brick by these decisions, one after another,” said Senate Democratic Whip Dick Durbin of Illinois. “Someone needs to call him on that, I hope on his side of the aisle.”

Asked to respond to the Democrats casting McConnell as a partisan villain, Republicans close to the majority leader laughed.

For one thing, they said, he doesn’t care what people think of him. The walls of his Senate office are covered in unflattering political cartoons of him from over the years, and at one point he started answering the phone as “Cocaine Mitch” in reference to a now infamous campaign ad from a failed Republican Senate candidate in West Virginia.

“I’ve been around a lot of politicians in my career and most of them are sensitive to every little thing. And he is sensitive to nothing,” said Jennings. “In terms of skin thickness? Level 10.”

Allies also scoffed at the suggestion that McConnell has ever been anything but consistent, saying his love for the Senate and love of political gamesmanship are not mutually exclusive.

“I don’t think it’s inconsistent to be a strong institutionalist and also to be a partisan and someone who plays to win,” said Law.

Josh Holmes, another former chief of staff and longtime political adviser, agreed, describing the majority leader as “ruthlessly effective” who has “absolutely” relished the process of strategizing around the impeachment trial.

“He is absolutely committed to winning, whether it be for his constituents and his members and for the country,” Holmes added. “Conservative ideology is something he’s committed to win.”

Building his case

During the impeachment trial, McConnell has sat almost perfectly still for hours at a time, hands folded in his lap, staring straight ahead. His focus is notable among other lawmakers who slouched, stretched, snacked, made faces, scribbled on legal pads or fended off sleep.

He has spent the past several weeks building the case he hopes to win by criticizing these House Democrats on the Senate floor for a “slapdash” political exercise motivated by their hatred of the president.

“The framers built the Senate to provide stability,” McConnell said during a speech on the Senate floor in late December. “The Senate exists for moments like this. That’s why this body has the ultimate say in impeachments.”

If McConnell has his way, he will orchestrate the ultimate victory: an acquittal of the president with no Republican defections.

“He is a significant strategist and very closely held,” said Sen. Roy Blunt of Missouri, a member of the Senate Republican leadership team who conceded he still sometimes has trouble interpreting McConnell’s moves. “Everything is not always everything it seems to be.”