Story by DEB ERDLEY and MEGAN TOMASIC

Oct. 9, 2022

As a father of four, Tim Briggs considered it common sense that schools would test for radon.

As a state lawmaker, he was appalled that every school doesn’t, and he has made it his mission to do something about it.

A months-long Tribune-Review investigation found that most schools in Southwestern Pennsylvania do not regularly test for radon, the odorless, colorless, radioactive gas found here in some of the highest concentrations in the nation.

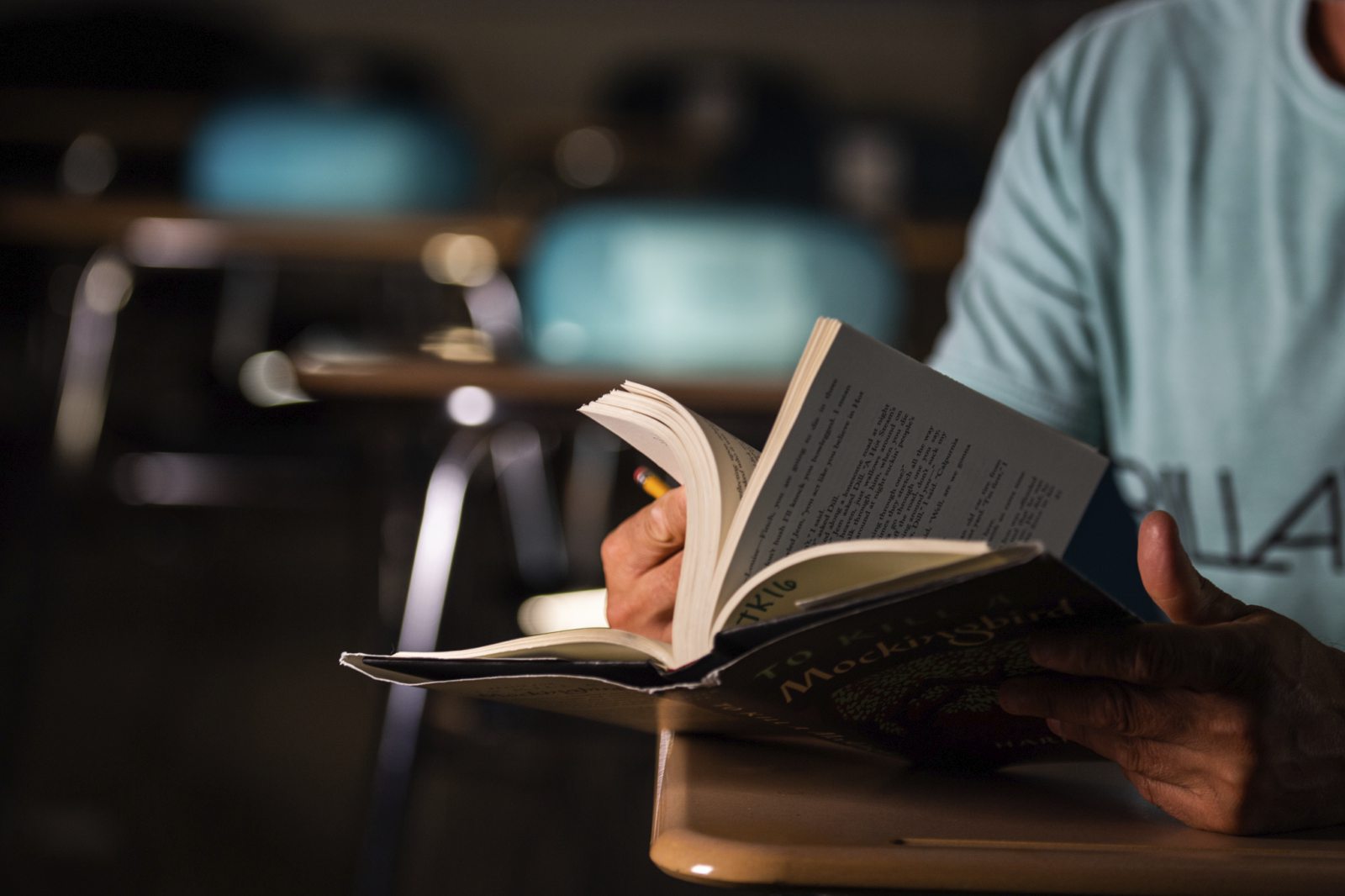

At risk is the health and safety of the state’s nearly 1.7 million school children — in addition to teachers and staff — who spend upward of 1,000 hours a year in classrooms, said Briggs, a Montgomery County Democrat.

“You don’t hear anything about (radon) until someone you know is affected by it,” he said, “and by then it’s too late.”

Briggs has introduced five bills in the past decade requiring school districts to test for the gas, whose deadly effects can emerge decades later in the form of lung cancer in some people, according to medical experts. Each time those bills failed, Briggs vowed he wouldn’t give up until he sees laws on Pennsylvania’s books like those in other states.

Radon is the second-leading cause of lung cancer after smoking, according to the American Lung Association. It seeps into basements through cracks in walls, foundations and other openings.

Medical experts link radon to at least 21,000 lung cancer deaths annually nationwide and more than 1,400 in Pennsylvania, which has the third-highest levels of radon in the country, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Children are particularly vulnerable.

For them, the risk of developing radon-induced cancer later in life is twice as high as adults with the same exposure because youngsters’ quickly changing bodies and rapid breathing rates translate into larger doses of radiation, researchers found.

Children exposed to radon plus tobacco smoke are 20 times more likely to develop lung cancer, researchers found.

Yet testing requirements have failed to gain traction in the General Assembly and among many school districts.

According to the Trib’s investigation:

• Requests filed under the state’s Right to Know Law with school districts in a four-county region of Southwestern Pennsylvania revealed that nearly 70% had not tested for radon in the past five years, the interval used by states with school radon testing laws in place and by Briggs in each of his failed bills.

• Many of the districts that had not tested are located in communities where state environmental monitoring identified dangerously high average radon levels, according to a review of state records.

• No records of radon testing at any time in the past were maintained by many of the school districts surveyed.

• Although school districts are required to report to the state Department of Education about a number of safety issues, no records regarding radon testing or repairs to mitigate high levels of radon are maintained by the department.

• Some school officials say they lack funds needed to test for radon — about $1,500 per building — but groups offering grants to conduct testing say it’s difficult to “give away” the money to districts to complete the work.

• Partisan politics and battles over who will pay for radon testing and mitigation have torpedoed attempts to pass school radon testing bills in Pennsylvania, supporters of the bills contend. Seventeen states have enacted various radon-related laws. Bills introduced in Pennsylvania have died in committee without a hearing or committee vote.

Of the 61 school districts surveyed by the Trib, those with no records of testing ranged from larger districts such as Upper St. Clair and Greater Latrobe to smaller ones such as Jeannette and Monessen.

The region’s largest district — Pittsburgh Public Schools — had no record of testing in the past five years.

Others said they had not tested for anywhere from six to more than 30 years ago.

Nineteen of the 61 districts surveyed completed testing within the past five years, with many taking steps to mitigate radon found at or above the level of 4.0 picocuries per liter of air that is deemed a health hazard by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The Yough School District is one of the districts comprising communities where the state Department of Environmental Protection reported radon well above the level deemed unsafe by federal officials.

Average basement radon levels measured 8.4 picocuries per liter of air — more than two times the acceptable level — in communities making up the school District, according to a state website recording radon levels.

But Yough has not tested for radon in the past five years, according to results of the Trib’s survey. Like many other districts, radon testing has not been part of the district’s safety routine.

“Radon, in my experience, hasn’t been included in any air quality testing even in the previous districts where I worked,” said Anthony DeMaro, newly appointed superintendent in the district. “If this is something our district needs to look at, just in anticipation of these bills (that might be introduced in the state Legislature), that is something we would take seriously.”

A breakdown of the state’s radon monitoring program is available on a database containing results of millions of tests performed by private property owners and licensed professionals. The average results for each community are available online by ZIP code.

Experts point out that just because a building or home has high levels of radon does not indicate that every structure in that neighborhood or community will have high levels. But testing is warranted, they say.

The state also found high levels of radon in communities making up the New Kensington-Arnold School District, where tests found average basement radon levels of 5.7 picocuries per liter of air and a first-floor average of 6.0. No testing occurred in the school district in the past five years.

Christopher Sefcheck, who just began his second school year as superintendent, said he is familiar with radon testing from his last position with the Bethlehem-Center School District, where testing for radon and lead in drinking water was done with a grant.

He said he would meet with the facilities and grounds director to “see what has to be done” regarding radon testing.

In some districts, radon testing has not moved beyond the discussion stages.

The state found average basement radon levels of 5.9 picocuries per liter of air and a first-floor average of 7.8 in the communities making up the Highlands School District.

Chris Reiser, buildings and grounds supervisor for the district, said there have been internal discussions about testing, but no action has been taken.

Dante Pope, who has a son in middle school and a daughter in fourth grade, said he doesn’t understand why Highlands has failed to move forward.

“(Radon) is something that needs to be addressed,” Pope said.

He said any investment in testing would be “minuscule” when the health and safety of children is in question, particularly when dealing with a proven cancer-causing agent such a radon.

Although lawmakers have not reached a consensus about radon, the message from the state’s environmental agency is clear.

“Inaction can mean increased exposure to radon, which in turn can increase the risk of lung cancer,” DEP spokeswoman Deborah Klenotic said. “The risk of lung cancer is associated with longer-term exposures … so the longer someone waits to test for radon, the higher the risk.

“DEP believes it’s important for all schools in Pennsylvania to test all frequently occupied, ground-contact rooms during the school years and would like to see legislation that would require testing and, if necessary, remediation.”

She said many states, such as neighboring West Virginia, already have this requirement.

Once a school has tested, it’s important to retest, state and federal officials said.

Just because a structure produced a low test level once, that does not mean that level will remain low. And installation of a mitigation system does not mean that further testing will not be required, according to federal guidelines.

That hasn’t happened in the Ligonier Valley School District, where state monitoring showed average community basement radon levels of 8.7 picocuries per liter of air, more than twice the federal action level. The first-floor average was 6.3, records show.

“All of our buildings were tested in the ’90s during renovations, but we do not regularly test,” said Ligonier Valley Superintendent Timothy Kantor. “We replaced our HVAC system in all of our buildings four years ago …

“We have not had discussions specifically concerning radon testing, but I plan on researching with our building and grounds director along with consulting county superintendents of what they do in their districts concerning radon testing and mitigation.”

One expert believes the invisible nature of radon and the fact its health effects are delayed for decades lead many to ignore it.

“If you don’t measure it, there’s nothing to fix. The health risks are delayed, which reduces the perceived risks,” said R. William Field, professor emeritus of occupational and environmental health at the University of Iowa, who estimates that a half-million Americans, including a large number who have never smoked, have died of radon-induced cancer since the 1980s.

Field, one of the nation’s foremost authorities about the effects of radon gas on humans, said lung cancer often remains dormant, sometimes exploding into a lethal health threat decades after exposure to radon. He added that there are currently no diagnostic tools to definitively link any one case of lung cancer to radon, but researchers have strong evidence tying it to lung cancer in nonsmokers.

David Trent lives each day with the heartbreak of what happens years after high levels of radon are ignored.

He graduated in the spring from Pine-Richland High School without his mother, Helena Lin Trent, there to see it.

A nonsmoker, she was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer in 2018. The Tai chi teacher and entrepreneur in website design and marketing died 20 months later at 47.

Trent, his father and doctors believe her cancer was linked to her childhood in China, where little attention was paid to radon testing.

Shortly after his mother’s death, Trent and his friends formed a nonprofit, RnFree, to mail radon kits to homeowners across the country.

In imploring school districts and state lawmakers to act, Trent recalled the sorrow of losing his mother at such a young age.

“It really hurts to be part of the 21,000 who have witnessed this firsthand,” he said.

Some school districts in the region — Hempfield Area, Kiski Area, Pine-Richland and Norwin, to name a few — are taking a head-on approach to dealing with radon.

Hempfield Area conducted districtwide radon testing, its first since 1995, this past spring at a cost of about $12,000. The tests, conducted in advance of a $100 million renovation project, found five areas slightly above the federal trigger level.

Superintendent Tammy Wolicki said officials will take whatever action is necessary to address those issues.

Pine-Richland, Kiski Area and Norwin participated in an ongoing radon testing grant program run by Women for a Healthy Environment and the Green Building Alliance with funds from the Heinz Endowments.

When radon above the federal safe level was discovered in several Pine-Richland elementary classrooms, officials moved quickly to retest and install mitigation systems, then posted the results on the school’s website.

Kiski Area facilities director James Perlik said that kind of transparency is vital.

“We qualified for the grant, so I went to the administration about it and we did it. Kiski Area’s buildings, including its 100-plus-year-old elementary school building in Vandergrift, all tested well within the EPA’s safe range,” Perlik said.

Testing at Norwin revealed radon above the federal action level in the middle school auditorium and stage as well as several classrooms and music rooms at Hillcrest Intermediate School.

Superintendent Jeff Taylor said officials are awaiting estimates for remediation work.

“I feel like radon testing is extremely important. I’m kind of disappointed that it is not required (to do) testing for the school districts,” Taylor said. “This impacts thousands of children across Pennsylvania, and it can affect adults who work in those classrooms all day as well.”

Fewer than two dozen school districts applied for the grants that helped Hempfield Area, Pine-Richland, Kiski Area and Norwin complete testing.

“I think honestly it is fear of the unknown that is delaying schools from participating in the program,” said Michelle Naccarati-Chapkis, executive director of Women for a Healthy Environment. “We recognize that schools in the last two years have had a lot of other issues to address in terms of online learning and technology. But we’ve tried to make this process straightforward to ensure that it is not burdensome.”

Many parents, aware of the dangers of radon in their homes, said they assumed their school districts were testing as part of routine safety checks.

Aimee Hogg of Unity, whose daughter is a junior high student at Latrobe, was stunned to hear that officials there said they did not test for radon.

“I am furious that they do not test … especially considering how much below ground level our high school building is,” Hogg said.

Hogg wondered what she was exposed to as a student and later as a teacher for 18 years at Hempfield Area High School.

“I guess what is most concerning for me is why they’re not testing. … I know this can have some bad repercussions as far as lung cancer,” said Rachelle Cancilla, a nurse at UPMC and the mother of a Franklin Regional High School student, one of the districts that had not tested in the past five years.

Cancilla said she and her husband just tested for radon at home after seeing a news story about the importance of testing as people set up offices in their basements.

“If my husband’s going to be working there (in their basement) four or five days a week, we obviously would want to get it taken care of,” Cancilla said. “I’m definitely not concerned about the costs. I’m hoping the school district would follow the same logic.”

• Pennsylvania has a unique geology that puts residents at higher risk for radon exposure than in other states.

• Radon is in the highest class of carcinogens — substances capable of causing cancer in humans.

• The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency warns Americans that there are no safe levels of radon and recommends remediation if levels are at or above 4.0 picocuries per liter of air. The agency also recommends that Americans consider remediation if levels are at or above 2.0 picocuries per liter of air.

• About 98.5% of the counties in Pennsylvania are designated in the two highest radon risk areas by federal officials. About 73% of the counties are in the top risk area, meaning their average radon levels are more than 4.0 picocuries per liter of air.

• The levels considered “safe” can vary from country to country. In Canada, any level at or above 2.0 picocuries per liter of air is considered too high and requires immediate remediation.

• A federal risk assessment of radon showed that a level of 4.0 picocuries per liter of air in a home is considered five times more likely to result in a lung cancer diagnosis when compared with the risk of dying in a car crash.

• Federal officials estimate that 1 in 5 American classrooms have a radon level at or above 4.0 picocuries per liter of air.

• Radon is the second-leading cause of lung cancer, costing the United States more than $2 billion annually in direct and indirect health care costs.

• Radon has no immediate symptoms that will alert someone of its presence. It takes years of exposure before any problems become apparent.

• EPA guidance suggests homes be tested for radon every two years.

Sources: Women for a Healthy Environment; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; American Lung Association

Deb Erdley and Megan Tomasic are Tribune-Review staff writers. You can contact Deb at derdley@triblive.com and Megan at mtomasic@triblive.com.