As Gov. Tom Wolf prepares to leave office, there is one thing that drove him into the governorship that awaits him when he gets home: his beloved 2006 Jeep Wrangler.

The Jeep, a stick shift, of course, that Wolf’s daughters joke he bought during his midlife crisis, starred in his first gubernatorial campaign ad in 2014 and helped him become a household name.

When he climbs into it after Jan. 17, he won’t be pondering his vision for Pennsylvania. He can reflect on the legacy he left behind for the commonwealth, a significant investment in education, beer and wine sales in grocery stores, legalized medical marijuana, or adding four new state parks to a system that hadn’t seen an expansion in nearly two generations.

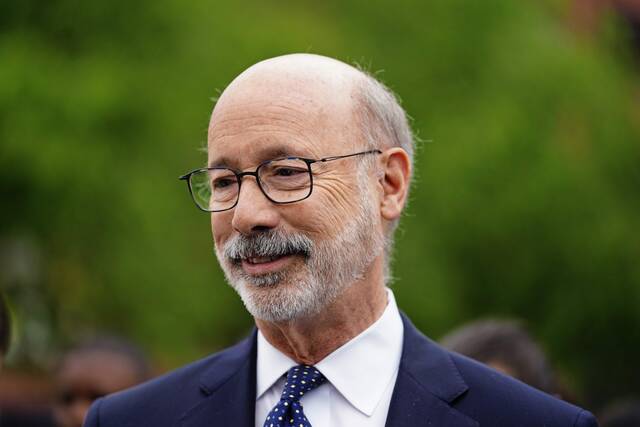

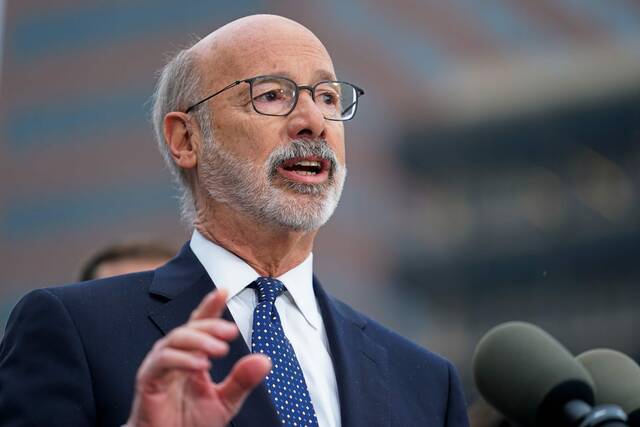

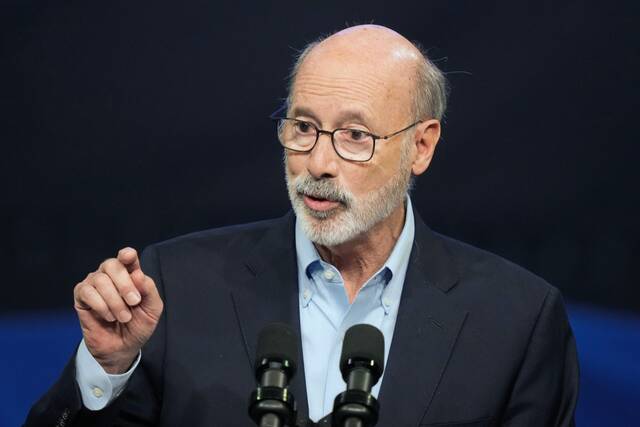

Wolf, a Democrat, recently sat down in his ornate office on the Capitol’s third floor to share some thoughts about his eight years in office, his dealings with a GOP-controlled legislature and his thoughts about some of the work he left unfinished. Through that conversation, it became clear he considered serving as governor of the nation’s fifth most populous state a privilege and, despite some challenging moments, he thoroughly enjoyed the job.

As for the lasting accomplishments of his time in office, he settled on three: his administration was devoid of any major public corruption scandal; major advancements were made in funding for public schools; and he leaves the state on what he believes is a much firmer fiscal foundation than he found it.

“An honest administration”

The first thing he did was bar state employees under the governor’s jurisdiction from taking any freebies. Wolf famously would drop a dollar on conference room tables when he visited newsrooms and was offered a bottle of water.

“I think that set the tone for integrity,” Wolf said. “So, this has been an honest administration.”

It wasn’t always smooth sailing though, or even transparent: Wolf had an ugly end to his forced match with Lt. Gov. Mike Stack after charges that Stack and his wife had been taking advantage of, and sometimes abusive towards, their state-paid staff. Then there were mysterious departures of several high-ranking administration appointees, including former Secretary of State Pedro Cortes and Adjutant General James Joseph.

Other appointees left after some glaring blunders – most prominently, his Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar departed after officials there missed a public notice advertising deadline that delayed consideration of a long-sought constitutional amendment to help adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse.

But for the most part, the Wolf administration avoided any major personnel scandals, but he alienated and infuriated many Pennsylvanians with his response to COVID-19.

The pandemic

Without question, history will note Wolf’s managing of the public health crisis posed by Covid-19. According to state and federal data, the pandemic has claimed the lives of more than 48,400 Pennsylvanians. It was a scenario that he admits caught his administration flat-footed.

“We do tabletop exercises on a regular basis just to say what bad could happen here,” Wolf said. “That was something no one expected.”

Without a pandemic playbook at the ready, Wolf recounted conference calls with President Donald Trump, and governors around the country and understanding how everyone was in a read-and-react mode.

“We were all in very new territory,” Wolf said. “The thing that I tried to do is do what I felt was best from a public health point of view, not play politics. And to the extent that I made bad decisions, I did it with the best of intentions. To the extent I made good decisions, they were done because I think I was trying to do the right thing.”

He ordered most businesses to close, causing major upheaval. He ordered schools to shut down for in-person instruction. Restaurants were restricted to take-out only service. Interscholastic athletics and other kinds of community events were cancelled.

His administration’s contact tracing, masking orders and other mitigation efforts quickly ran into resistance from members of the public and Republican lawmakers whose offices were inundated with complaining constituents.

“I think the pandemic had a significant impact on a lot of things,” former House Majority Leader Kerry Benninghoff, R-Centre County, said. “It basically turned people’s world upside down. Anybody that’s in an executive office, no different than ours, is going to feel somewhat overwhelmed.”

Benninghoff considers Wolf’s response to the pandemic a tipping point in his relations with House Republicans (and some in the Senate), who strenuously challenged the governor’s use of executive power in handling the pandemic response and his delegation of decision-making authority to his former health secretary, Dr. Rachel Levine.

“I do think it made things probably difficult for the remainder of his tenure here because there was such a disparity in opinion over how to handle it,” Benninghoff said. “I’m sure he didn’t like us pushing back or arguing with some of his edicts and some of his decisions.”

Former Senate President Pro Tempore Jake Corman, R-Centre County, the only lawmaker who held a top legislative leadership post throughout Wolf’s entire tenure, said he too didn’t agree with everything the governor did when it came to the pandemic. Still, he said he holds onto the belief Wolf was doing what he thought was best for Pennsylvania.

“It wasn’t like a political motivation on his part. It was like this is what he believes are the dangers of COVID and what he thought the response from government” should be, he said. “I didn’t take that as sort of thumbing his nose at us. It’s something that was never dealt with before. It was what he was being advised toward and away he went.”

Wolf said a lot of important lessons were learned over the pandemic years. Personal protective gear has been stockpiled to avoid the scramble to find gloves, masks and gowns when the next pandemic arrives.

“But will there be something else we didn’t think of that didn’t come up in the last pandemic?” he said. “We just don’t know. We’ve got to be prepared to try to deal with these unknowns.”

He sees that as one of the biggest challenges for whomever is in the governor’s office. That’s why he advised Gov.-elect Josh Shapiro to expect the unexpected and to prepare as best he can.

“Those are the things that I think a responsible government needs to do and so I’ve suggested to Governor-elect Shapiro that he keeps doing those table-top exercises,” Wolf said. “Keep trying to think about disaster that could befall Pennsylvanians and ask yourself: ‘What can the governor do to help?’”

Education funding

“I ran in part because I thought the commonwealth needed to do more in the education space, and over the last eight years we’ve invested – if you include the state system – $3.7 billion [in new annual spending} … an all-time record by a lot,” Wolf said.

Over the past eight years, the state’s basic education subsidy – the main vehicle for state aid for regular classroom instruction and other day-to-day operations in K-12 public schools – mushroomed from $5.5 billion when Wolf took office to $7.6 billion as he leaves, an annual boost of 38 percent.

“Giving our children a good education is an investment in our future workers, leaders and entrepreneurs. It’s an investment in an educated commonwealth and a roaring economy for decades to come,” Wolf said in a post-budget news release.

While landmark education funding will be his greatest legacy, Wolf didn’t get everything he had on the education wishlist.

Wolf tried unsuccessfully to raise the state’s $18,500 minimum teacher’s salary – that has stagnated for over 30 years – to $45,000 and he sought to lower costs of charter schools on the state’s 500 school districts.

He made a couple of attempts to entice new college graduates to stay in Pennsylvania by offering students at community and state-owned colleges loan forgiveness if they stayed here for at least as many years as they got the money. The idea never gained footing with the GOP-controlled legislature.

But he did manage to invest a historic amount of money in the State System of Higher Education as it undergoes a major transformation, consolidating universities and swiftly moving toward allowing students of any PASSHE school to enroll in classes at any campus in the network.

Wolf admits there is still work to do on the education funding front, namely continuing to increase the state’s share of the load to ensure that all schools are fairly and adequately funded.

Until that’s done, he said, “we’re not going to get the property tax relief we need. I think the commonwealth is now positioned to continue to do what we’ve started – that is keep funding in public education and give local property taxpayers some relief.”

He also shared some frustration that education isn’t in a better place as he prepares to leave office with the scars of remote learning showing up in last year’s state assessment scores and the state facing a teacher shortage that some blame on the pandemic and others to a lack of support educators receive.

“There’s no question about it the pandemic, just reinforced [and] reaffirmed the notion that in-class education is what we need. We did lose something for kids not being in school,” Wolf said. “I’m not sure how standardized tests capture that but I think it wasn’t a surprise to anybody that we lost something.”

As for the teacher shortage, he said that’s another reason why investing in education is important to ensure educators are getting their due.

Fiscal stability

“We had $200,000 in the Rainy Day Fund when I arrived. We have $5 billion now. We had a $2 to $3 billion budget deficit when I arrived. We now, this budget has a $5.3 billion surplus baked in and as of the end of November we’re running ahead of that budget on the revenue side,” Wolf said.

“So I’m proud of the fact that we’ve done everything honestly, competently, and I think we’ve done some smart things.”

The markedly improved fiscal health of the state reached the point where lawmakers and Wolf were able to collaborate on a schedule to begin to reduce the state’s corporate net income tax rate – long one of the nation’s highest – earlier this year.

Benninghoff takes shared credit for accomplishing the change that he hopes makes Pennsylvania more attractive for companies – and doing it without any “backdoor tax increases” Wolf and Democrats fought for to offset some of the revenue loss from lowering the corporate tax.

The current fiscal stability is in part due to unprecedented amounts of federal aid released in the wake of the pandemic to individuals and businesses to try to stave off the worst of an instant recession, and to state and local governments to help spur a recovery.

Still, even Republican legislators agree Wolf is leaving the state’s fiscal health in better shape than he found it.

“The budget’s in probably the best place it’s ever been, at least in my time,” Corman said. “We made historic tax cuts, made investments in education and we have a historic amount of money in the Rainy Day Fund. That’s a pretty good day.”

Wolf expressed disappointment that his administration did not get a major state-level infrastructure program passed: his big second-term initiative, “Restore Pennsylvania,” called for a massive state bond issue to cover everything from flood prevention efforts to expanded broadband access to bridge repairs, all paid for by a new state tax on natural gas production.

Republican lawmakers, historically resistant to additional taxes on Pennsylvania’s gas resources, rejected the plan.

However, many of the same projects that Restore Pennsylvania would have covered will now be fully-funded by portions of the federal infrastructure package enacted earlier this year.

Politics

Wolf, barred by the state constitution from seeking a third term as governor, found himself in a strange political purgatory this year as Attorney General Josh Shapiro, a Democrat, and a roster of Republicans sought to replace him.

Republican gubernatorial nominee Doug Mastriano, a state senator from Franklin County, routinely savaged Wolf’s record, trying to hold he and Shapiro up as poster boys for a “radical left.”

On Nov. 8 Shapiro had scored the biggest open-seat governor’s race victory in decades, and the Democrats had become the first party to win three governor’s race elections in a row since World War II.

Where some incumbent politicians might have seen that as a personal vindication, Wolf said it was Shapiro’s win.

“I think we had some good candidates and the voters, I think, made the right decision,” Wolf said. “I agree with the changes that we saw in this past election, but I don’t see it as a personal vindication. I think voters out there are looking for people who are honest and who will do the things that make their lives better and do it in a fiscally responsible way.”

Wolf said he gets all the personal satisfaction he needs from knowing that he gave this job his best effort for the past eight years and, in his view, got some good results to show for it.

“I think that’s the way it should be,” he continued. “I don’t think you should take this stuff personally. I ran a True Value Hardware store at one point in my career and, you know, you can’t take customer complaints personally. Some people like the product. Some people don’t. And you learn to live with that.

“If you’ve made a mistake, you own up to it and you do something about it. And that has happened in the last eight years. I’ve made mistakes. But, when you just disagree with somebody that’s their prerogative. And you recognize that and move on.”

“Tom Wolf was an honest broker,” Corman said. “That’s all you could ever ask for in government is dealing with somebody honestly. You’re not always going to agree. In divided government, you’re certainly not going to agree a lot. There were many deep divisions but he was always honest about the divisions. He was always honest about where he could go, where he couldn’t and that’s all you can ever ask for in government.”

Relationship with the Legislature

Corman’s post-game reflections notwithstanding, Wolf’s relations with the Legislature were a real-life political roller-coaster ride.

Wolf made some national news during his first season in office by paying visits to rank-and-file legislators of both parties in their Capitol offices, and inviting others to the Governor’s Residence.

“It’s a very smart thing,” Steve Miskin, spokesman for House Republican leaders at the time, told The Philadelphia Inquirer. “He’s termed himself a newcomer in this building, and it operates on personal relationships. Even if they don’t agree on the issues, at least they can talk across the table.”

But the honeymoon lasted to about the time Wolf dropped his first budget proposal in March 2015, a sweeping plan that would have dramatically increased state funding for schools in one year by increasing the state income tax in exchange for cuts in local property taxes.

That and other issues started a year of increasingly bitter budget battles that hit their nadir in February 2016, when, delivering his second budget plan to the Legislature even before the first one was resolved, a finger-wagging Wolf told the lawmakers he’d visited with the year before: “If you won’t face up to the reality of the situation we’re in, if you ignore that time bomb ticking, if you won’t take seriously your responsibility to the people of Pennsylvania – then find another job.”

By another metric, Wolf has vetoed 66 bills since 2015, believed to be more than any other governor since former Gov. Milton Shapp, who served in the 1970s.

Allies and supporters often pointed to Wolf’s veto pen as his greatest legacy, arguing it preserved abortion rights, protected voting rights for all and blocked what some saw as unsettling attacks on transgender youths. Still, Wolf’s press office has noted the governor also signed 95% of the bills that came to his desk.

Among them, Wolf and the Republicans were able to negotiate some significant wins, most notably in education funding, legalizing medical marijuana, Medicaid expansions, liquor modernization, and key public pension reforms.

“I would have liked to have done a couple other things but you measure everything with pluses and minuses,” Corman said. “I think in the eight years he’s been here, there’s more pluses than minuses.”

The last few years, however, may be remembered most for titanic battles about the extent of the governor’s powers, exacerbated by the pandemic.

After seeing Wolf veto or threaten to veto GOP-offered bills to repeal some of his COVID-19 mitigation efforts or administration-backed regulations, Republicans took matters into their hands to shift the balance of power away from the executive branch and into the legislature.

They advanced a constitutional amendment, which voters ratified in May 2021, giving the General Assembly the authority to end a governor’s emergency declaration with a simple majority vote. Shortly after it took effect, they used this power to end Wolf’s COVID-19 emergency disaster declaration.

Benninghoff considers that a significant accomplishment, adding it educated Pennsylvanians about how government can work.

“There are avenues around a governor who’s going to veto, veto, veto,” Benninghoff said. “That’s a proud moment for us.”

Benninghoff also credited Republicans with tipping the balance of power in lawmakers’ favor on issues like limiting PennDOT’s power to impose mandatory tolls or user fees for new transportation projects; killing the charter school reform regulations that Wolf sought; and proposing a constitutional amendment that would allow the General Assembly to negate administrative regulations.

“It’s been a whole host of things over the last two and a half years … that has led to that balance being changed which is gonna obviously impact things for decades,” Benninghoff said. “I’m proud our caucus did a good job of saying well, it has to stop. This is enough.”

For the record, Wolf said he does not believe he was guilty of executive overreach.

But as if to prove his earlier point about not taking any of this personally, Wolf said he’s not holding grudges about the policy battles or his opponents’ at-times virulent criticism of his tenure.

“In a democracy, saying that they’ve disagreed with some of the things that I’ve done. Is that fair?” he asked, pondering a question about the last two years.

“Yeah, I think that’s the name of the game, isn’t it? We actually argue, debate and come up with things… I mean, sometimes I disagree with where they are, and I’ve shown that. And sometimes they disagree with where I am, and they express that as well.”

Pennsylvania’s future and the limits of power

Wolf, like governor’s before him, found himself running a state that is one of America’s slowest-growing – whether your measure is job creation, population or most anything else but median age.

Wolf said he knew coming in that he didn’t have some kind of magical superpower to change those paradigms overnight, but he does believe there are some grounds for optimism about Pennsylvania’s long-term future.

They trace back both to things that are baked in – Pennsylvania’s strong roster of colleges and universities and richness of natural resources – and things he and his predecessors have tried to carefully nurture through policy decisions.

“When I first started running, I would go out to Pittsburgh and sort of ask the typical political question ‘What’s the biggest problem here?’ and they’d say: ‘We need jobs.’” Wolf recalled. “You go out to Pittsburgh now and it’s: ‘We need people.’

“Pittsburgh is not a Rust Belt city anymore. It’s the biggest city in Appalachia, but it’s actually one of the most livable cities in the world by some estimates. The Southeast has become a hub of the life sciences. And Pennsylvania agriculture is finding some really new innovative ways to bring food to peoples’ table.

“So I think these kinds of changes take a long time, but I don’t think that the road we’re on right now is a road that’s either static or downward… I think we’re on the way to being the high-tech place that I believe Pennsylvania is capable of.”

Citing Pennsylvania’s affordable cost of living, its strong higher education network and its proximity to the richest markets in America, Wolf said “we have a lot of things going for us and I think the rest of the world is waking up to this.”

“But you can’t snap your fingers and make anything happen in this job. I didn’t expect that and I don’t think anybody should come into this job expecting to do that.”

It’s a Jeep thing

Now 74, and having won a bout with prostate cancer while in office, Wolf said his retirement will be genuine.

“I’m going to read, eat and sleep and spend time with my grandchildren… This is my understanding – I might be wrong – but people actually do retire. And that they don’t necessarily have a job when they do that. That’s what I’m looking forward to.

“I’ve been working all my life.”

But is it that easy to walk away from the limelight?

“Maybe I’m different,” Wolf said. “I mean I have been in leadership positions in the private sector. I was a Peace Corps volunteer on my own. I was an academic…. So I’ve been used to that” busyness. “But I’ve also really enjoyed the pleasures of reading and eating and sleeping and spending time with my family.”

And, he says, he’s looking forward to the pleasures of climbing back into that Jeep which, while not nearly as prominent as it once was, also survived the past eight years.

Wolf said his Jeep is in the garage now, getting road-ready for his post-government life. (Sitting governors are strongly discouraged from driving themselves, for insurance and other reasons.)

“I’ll be driving it soon again, and I just renewed my license, Real ID, yesterday, and so I’m ready,” he told PennLive. “I also took driving tests and lessons from the Pennsylvania State Police so both [first lady] Frances and I are ready to hit the road again.”