Millions of doses of the covid-19 vaccine have shipped around the nation, but virologist Sham Nambulli’s work is far from done.

He rises daily in his South Fayette home, hops into his Toyota Camry and heads north on I-79 toward the Parkway West. His destination is the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Vaccine Research in Oakland, where Nambulli will join his laboratory colleagues in the local effort to create a long-lasting covid vaccine.

The world is worn down by covid surges, shutdowns and public discourse. The death toll from the pandemic has already crossed the 300,000 threshold in the United States. Still, it’s hard for Nambulli to contain his excitement about the future as he approaches the Fort Pitt Tunnel.

“As a virologist and a scientist, going through the pandemic phase is extremely thrilling,” he said. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Sometimes it feels like it’s too much. But it’s beneficial for me as a scientist, and I know I am doing this for a good cause.”

Despite the availability of several covid vaccines, there are at least 180 more in production around the world. Scientists are still racing to find the safest, most-effective tool to defeat the deadly illness. They will learn from the available vaccines and the others in production.

Nambulli, 38, and his colleagues are developing a covid vaccine that contains live measles virus and proteins from the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. In scientific terms, it’s known as a recombinant vector vaccine.

Pitt’s vaccine is designed to produce antibodies to both measles and the coronavirus that causes covid-19. The Pitt vaccine is engineered to teach the immune system how to fight the coronavirus. If it works, it won’t require ultra-frigid temperature storage, like the Pfizer vaccine, and will be easier to keep in remote locations.

The vaccine should also produce T cells that remember the pathogen and make antibodies specific to the coronavirus if the body encounters it in the future. These antibodies neutralize the virus by latching onto the spike protein and preventing the virus from entering the cells, which keeps a person from becoming ill or further spreading the virus.

The idea is to take genes from the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and put them into the measles vaccine.

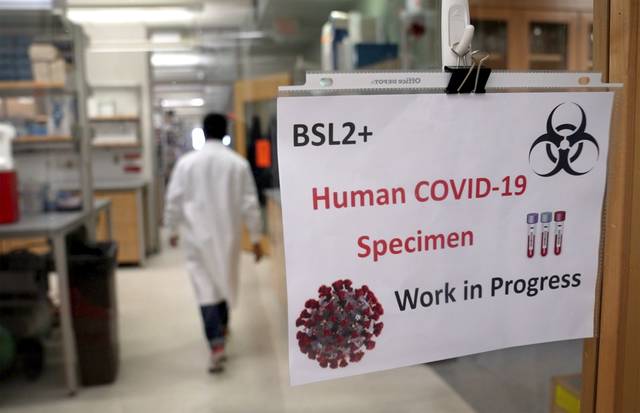

“It’s mixing one virus with another to create something that would not exist outside of the laboratory,” said Paul Duprex, director of Pitt’s Center for Vaccine Research. “But we can put it to really good use for public health.”

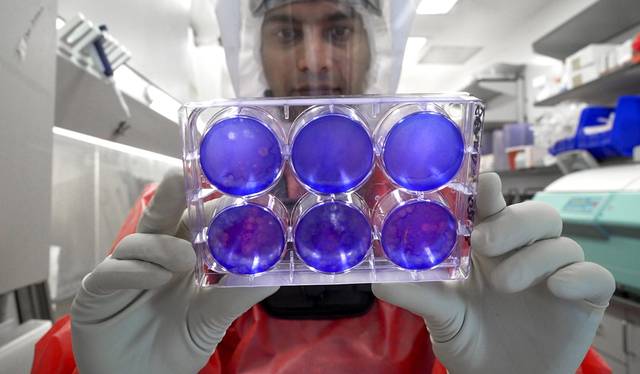

From there, researchers can analyze whether vaccine test subjects begin to create antibodies in response to the vaccine.

“It’s exactly the same as how the measles vaccine would behave,” said Natasha Tilston, one of Nambulli’s colleagues in Pittsburgh. “It is just being engineered to carry something that isn’t measles.”

Tilston, 36, worked as a postdoctoral researcher in the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL) at Boston University. She met Nambulli in Boston as both worked under the mentorship of Duprex, a professor of microbiology and molecular genetics.

In 2018, Pitt hired Duprex as director of its Center for Vaccine Research. He brought Tilston and Nambulli along with him. Little did they know they’d be leading a local charge to create covid-19 vaccines two years later.

“I feel privileged because it’s what we have all been training to do,” said Tilston, who settled in Squirrel Hill, much closer to the lab than Nambulli. “If you take it from a virology perspective, I actually get to try and help make a difference. This group I am in has been able to accomplish a lot.”

She doesn’t necessarily view their work as a competition with other researchers. Everyone, she said, is seeking the same goal.

“We’re all fighting and racing against the virus,” she said. “We have to continue what we are doing. There’s still a lot to learn.”

Duprex agreed.

“Typically, vaccines take 10-and-a-half years to develop,” he said. “So we are racing forward as vaccine developers. Competition is good because competition drives hard work. It drives creativity. It drives people to develop different approaches for vaccines. Because what we know is that the first vaccine that is produced might not be the best.

“In development of new vaccines it’s really important to have backups and backups and backups and backups. That’s why it is not a race.”

Duprex and his team are working with global vaccine maker Serum Institute of India for mass production.

Nambulli was born in Kerala, India. Before moving to Boston, he trained with Duprex at Queen’s University in Belfast, Northern Ireland. A bond was formed as they moved over the Atlantic Ocean to Boston, then Pittsburgh.

Duprex praises Nambulli’s “green fingers for science.”

“Nothing would be done without those green fingers who can grow the virus, manipulate the genetic material and make these recombinant, joined-up viruses that didn’t ever exist before,” Duprex said.

He said the work stems from Jonas Salk’s breakthrough with the polio vaccine in the 1950s at the University of Pittsburgh. Mass immunizations nearly wiped out polio throughout the world.

Decades later, Nambulli and his team are growing the coronavirus in large quantities and testing their vaccines on hamsters and monkeys to see if they generate the proper antibodies. They work with live virus behind layers of secure doors in spacesuit-type gear. Before handing the virus in the lab, Nambulli whips up a batch of disinfectant for protection against any potential spill.

But Nambulli is confident no mishaps will occur. He has those steady hands and green fingers. His home is full of indoor plants.

Before the pandemic, he loved to garden with his wife, Nikhila. In their backyard, and even out front, they grew tomatoes, okra, broccoli, cauliflower and eggplant among other things, including the Indian vegetable called bitter gourd.

His son and daughter, 7-year-old twins, are well aware of their father’s work and long hours.

In November, they sketched and colored images of the coronavirus while describing their dad’s mission. They talked about how they miss him on the days he departs for the lab before they wake.

“He is trying to figure a medicine or vaccine to help everybody,” says Nambulli’s daughter, Varadha.

His son, Vasudev, explained why: “Even kids, so they can go to school and play with their friends.”

The family support isn’t lost on Nambulli.

“They’re amazing,” he said of his wife and children. “They always say that they are very proud. I’m a family guy and I generally don’t go out. I spend a lot time with my wife and kids.”

They all see the bigger picture.

“It motivates me every day,” Nambulli said of the potential payoff. “The people I am collaborating with, we are all very thrilled and looking forward to how this is going to come out.”

Tilston said she never forgets that the world remains in the midst of a pandemic, and people are dying.

“We have a long way to go,” she said. “I feel very lucky to be able to contribute.”

Virologists and scientists across the globe working on various forms of the coronavirus vaccine feel a connection, Duprex said.

“It’s not just about Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the United States,” he said. “It’s about all of the world.”