There was never any question that Mona Pappafava-Ray and Lori V. Albright would follow in the footsteps of their fathers.

While the tool-and-die business has always been a male-dominated space, the two women — both of whom worked in their fathers’ shops right out of school — have emerged as standout second-generation family business owners in a thriving industry cluster that has pushed Western Pennsylvania into international prominence in sectors including aerospace, defense, automotives and energy.

The two companies — Albright’s Stellar Precision Components and Pappafava-Ray’s General Carbide Corp. — are part of a low-profile cluster of tool-and-die operations that developed quietly here during the last 70 years. Experts trace the cluster and its expertise back to Kennamental, which pioneered tool-and-die operations in tungsten carbide in Westmoreland County shortly before World War II when the now publicly traded corporation was a family business.

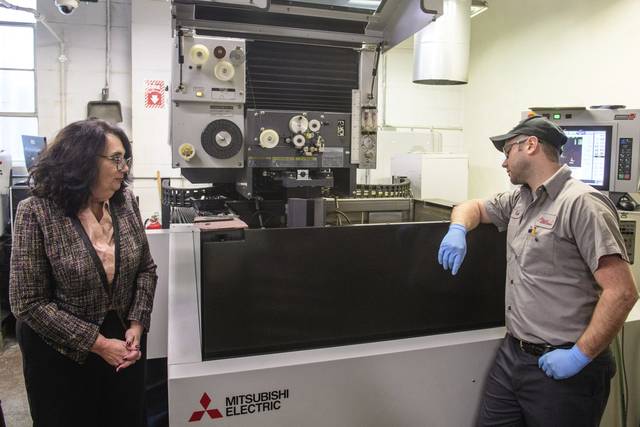

While the region’s tool-and-die shops may not fit the picture many associate with manufacturing — images of massive plant floors with hundreds of workers scurrying about — they are at the root of it. The 19,220 workers who make up Pennsylvania’s tool-and-die industry provide the highly specialized parts and tools that form the foundation for the success of countless manufacturers who turn out finished products here and abroad.

Albright and Pappafava-Ray have earned the respect of those who monitor the local economy.

“Not only are they doing well, I’d argue that they are among the best in the county. They would certainly be right up there. They’ve got deep expertise and both of the ladies who own them are incredibly competent, incredibly capable leaders,” said James Smith, CEO of the Economic Growth Connection of Westmoreland County.

The numbers speak to their expertise.

Pappafava-Ray’s company, with revenues of about $40 million a year, and Albright’s, with revenues of about $12 million a year, are among only 4.2 percent of U.S. female-owned companies with revenues in excess of $1 million a year, according to the National Association of Women Business Owners.

Soaring above others

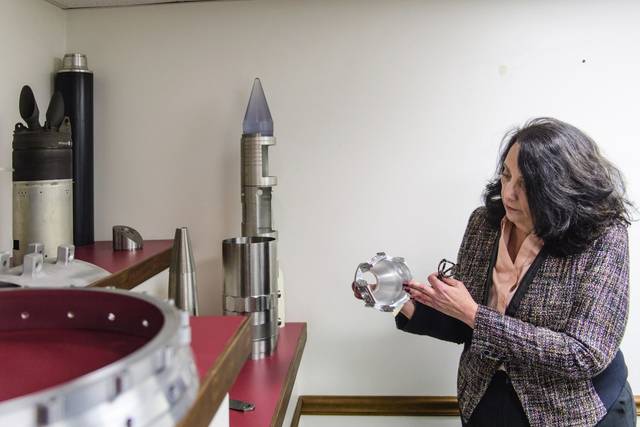

If there’s a satellite flying overhead, chances are the specialized high-precision parts that stabilize it as it soars into the ether came from Albright’s shop nestled in a valley at the outskirts of Jeannette. NASA’s workhorse Atlas 5 Rocket also relies on the shop for specialized parts.

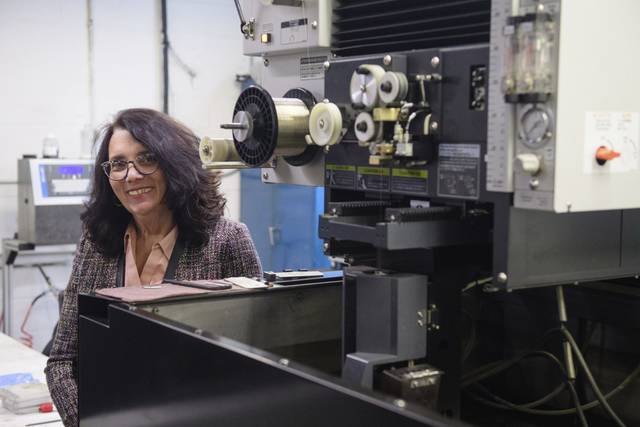

Pappafava-Ray’s Hempfield-based operation now boasts multiple specialty shops. Their products range from parts for the most common kitchen knife sharpener to one-of-a-kind components for the New Horizons Explorer that traveled to Pluto.

James Kunkel, director of the Small Business Development Center at Saint Vincent College, said the success of the two companies in the midst of a ring of tool-and-die companies illustrates one of the prime points of the industry cluster theory: that companies thrive in a highly condensed, competitive atmosphere.

“That competition drives everybody to do better. You either get very, very good at what you are doing or the next guy down the block is going to capture your market share,” he said.

Measurable success

While the U.S. Census Bureau reports women represent nearly half of the U.S. workforce, or 47.5 percent, they still comprise only 29 percent of the manufacturing workforce. As of 2017, the National Association of Women Business Owners reported only 1.2 percent of the nation’s female-owned businesses are part of the manufacturing sector.

Their role in manufacturing was even smaller back when Albright, now 58, and Pappafava-Ray, 56, first stepped on the shop floor decades ago, determined to learn all facets of the businesses that their fathers built.

Long hours, sleepless nights and a commitment to treat employees like family while keeping a close eye on finances has paid off for the women in charge.

“We’re now three times the size we were when my dad died in 2002. In some of our markets, we’re number one in the country,” Pappafava-Ray said.

Albright, who skipped college to go to work for her father in 1978 when he opened the plant, likewise has seen revenues grow. They are about six times what they were when her father, Mike Vucish Sr., handed over the reins in 2003.

‘Crazy worth ethic’

Along the way, Albright raised five children, and now counts a son and daughter among the third generation at Stellar Precision Components.

She didn’t go to college until 2013, when she attended Harvard’s three-year owners, presidents and managers program.

“That gave us some validation,” Albright said.

Her head for business was apparent well before she ever entered the Harvard program. A Penn-Trafford High School student in 1978, Albright was managing a cookie shop at a local mall when Mike Vucish Sr. told her he needed her to come to work in his new company.

Over the years, she learned every job in the shop as well as the office, determined to make the operation sing.

“There were years when we’d start out in January and I’d worry that we’d have to lay off everyone in February. But that didn’t happen. We got through.

“I definitely inherited a crazy work ethic from my father and mom. I wouldn’t feel right not being here, but everybody is still fed and everyone is still alive,” she said.

Pappafava-Ray began spending Saturdays at the machine shop her father launched in 1968 when she was about 10 and started filing and answering phones for him. By the time she hit college, she was keeping books for another family enterprise from her dorm room at Carnegie Mellon University.

She said she learned the value of treating employees like family from her father, Premo Pappafava, a second-generation Italian-American who knew what it was to struggle.

“He wanted to take care of everyone. He truly loved the people here. He knew we had more than one stakeholder: that the employees, the customers, the community and the bank were all part of it and that we were in it for the long run,” she said.

Following his example, when two deep recessions hit the industry in 2008-09 and 2014-15, rather than lay off employees, Pappafava-Ray looked for alternatives. There were pay freezes, pay cuts for management, reduced work hours and a freeze in 401K contributions.

When the economy bounced back, she said employees shared in the company’s rebounding fortunes.

Whatever their management secrets or people skills, it is apparent Pappafava-Ray and Albright have perfected the secret sauce that eludes many family businesses. A study by Deloitte found fewer than a third of all family-owned businesses make the transition into the second generation.

These Westmoreland County women not only made the transition, they are both on their way to celebrating 20 years of leading the companies their fathers founded.