Talking turkey since 1621: What was on the table at the first Thanksgiving

There is a lot of speculation and misinformation about the menu of the first Thanksgiving dinner, held in 1621 at Plymouth Colony in what is now Massachusetts.

Was turkey on the table? “We don’t think so,” according to npr.com.

“Turkeys are a possibility, but were not a common food in that time,” said newengland.com.

Or were they?

“I think it’s safe to say there was likely turkey at the first Thanksgiving,” said Malka Benjamin, associate director of interpretation and training at Plimoth Patuxet Museums in Plymouth, who speaks with some authority.

“We very much are the museum of Thanksgiving,” she said about the living history center and village that “brings to life the history of Plymouth Colony and the Indigenous homeland.”

“We have to look to those writing about the colony. Many writers talk about the abundance of turkeys,” she said.

Letters from the period refer to all kinds of fowl, among them ducks, geese and, in one instance, “innumerable” turkeys.

“Beyond bird meat, we don’t know what specifically they were eating,” Benjamin said. “There probably was venison on the table.”

It’s likely the table contained squash and a grits-like corn porridge called “sampe.” Shellfish, cranberries, currants, walnuts, chestnuts, beechnuts, pumpkins and beans would have been available, too.

History Channel adds lobster, seal and swan to the feast.

We also don’t know the specific date when this holiday took place, Benjamin said.

“It was a three-day harvest celebration,” she said. “We don’t know the precise dates, but we know that it was after the harvest was gathered, so it was late fall.”

Traditions of gratitude

How many people were there and whether the crowd included women and children are other subjects of debate. What isn’t in dispute is that the Pilgrims and their native neighbors, commonly referred to as Wampanoag, had cultural traditions of gratitude.

“The native people had a tradition of giving thanks daily and seasonally,” Benjamin said. “In England, they had the harvest home tradition.”

Each group also had a compelling reason to give thanks, she added.

“From 1616 to 1618, a terrible plague swept from Maine to Cape Cod,” Benjamin said. “We don’t know what it was, but the recent best CDC guess is that it was leptospirosis.”

Probably introduced by a European fishing exhibition, the bacterial infection produces fever, headache, bleeding, muscle pain, vomiting and other symptoms and can lead to kidney and liver damage, even death.

“Estimates are that 40% to 90% of the population was affected or perished,” Benjamin said. “Think about that culturally — those are the medicine people, elders who held the people’s history, warriors who are lost.”

After arriving at Plymouth in November 1620, the Pilgrims suffered a winter of hardship, with about half of their company of 100 succumbing to the effects of poor diet and harsh weather.

“About 50 people were left, half of whom were children,” Benjamin said. “These are both peoples with recent memories of significant trauma.”

Living side by side

In March 1621, the Wampanoag leader Ousameguin, usually referred to by his title Massasoit (which means “great leader”), met with Gov. John Carver at Plymouth to negotiate a mutual defense and trading pact. That spring, a group of Wampanoag settled across a brook from the Pilgrims to plant their crops.

“So they’re living all summer near each other,” Benjamin said. “Their world views are as different as night and day, and they don’t speak the same language; but when you’re living side by side, you get to know people a little bit.”

When they gathered for the harvest feast, Benjamin said, the ratio of Wampanoag to Pilgrims was at least 2 to 1.

People probably played games and, on the Pilgrims’ side at least, conducted military drills “because that’s the kind of thing the English do when they celebrate,” Benjamin said.

“An interesting detail is that Massasoit gifts five deer to the Pilgrims,” she said. “While deer is a common meat in New England, deer was a high-status meat in England, eaten only by royalty.”

The story of that first Thanksgiving traveled back to England in a letter to a friend from colonist Edward Winslow. In 1622, it was published in a book called “Mourt’s Relation.” It comprised less than two sentences in three pages of text about crops and life at Plymouth, Benjamin said.

Winslow’s account gained wider readership through Alexander Young’s 1841 compilation, “Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers,” so it’s unlikely that George Washington knew of it on Nov. 26, 1758, when he gave thanks with Gen. John Forbes near the smoldering ruins of Fort Duquesne — an event sometimes called Pittsburgh’s first Thanksgiving.

“I don’t think that (information) figured in until later, when people were learning the stories of the Pilgrims,” said Andy Masich, president and CEO of the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh.

Struggles and blessings

Forbes and Washington had arrived at the forks of the Ohio River in the midst of the French and Indian War, looking to rout the French stronghold.

“In November 1758, the French has seen the writing on the wall, that the British juggernaut was on its way,” Masich said. “Fort Duquesne was an earthen, wooden fort, so the French fired their magazine and burned anything they couldn’t take with them in their bateaus and canoes.”

Forbes named the place Pittsburgh after British Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder, and called for a day of public thanksgiving, Masich said, marked by both a religious service and a meal.

“They were giving thanks for having made it over the Allegheny Mountains and through the dense forests and having survived friendly fire and attacks by the French and Indians,” Masich said. “It was a relief at finally arriving at their destination at the forks of the Ohio River, as The Point was called then.

“Everyone would have been thinking of their personal struggle and how far they’d come and what they had to be thankful for — the blessings and bounty of providence — and Washington would have thought that way also,” Masich said.

The meal was maybe “not the best fare; they had their salt pork and beef and hardtack,” Masich said. “They probably traded with the local Indians, and there may have been some turkeys in the area, as it was a commonly eaten game bird.”

Menu notwithstanding, the day apparently made an impression on the 26-year-old Gen. Washington.

“Forty years later, Washington, now president, declared Nov. 26, 1789, to be a day of thanksgiving and prayer,” Masich said. “It was the first time Thanksgiving was celebrated under the new U.S. Constitution.”

Winslow’s account

A brief description of the 1621 Thanksgiving celebration, courtesy of Plimoth Patuxet Museums:

“… our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a more special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labors; they four in one day killed as much fowl, as with a little help beside, served the Company almost a week, at which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest King Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted and they went out and killed five Deer, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governor, and upon the Captain, and others. And although it be not always so plentiful, as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.”

— Excerpt (edited for clarity) from a letter written by Edward Winslow, Dec. 11, 1621, as printed in “A Relation or Journall of the Beginning and proceedings of the English Plantation settled at Plimoth (now known as Mourt’s Relation).” London: John Bellamie, 1622.

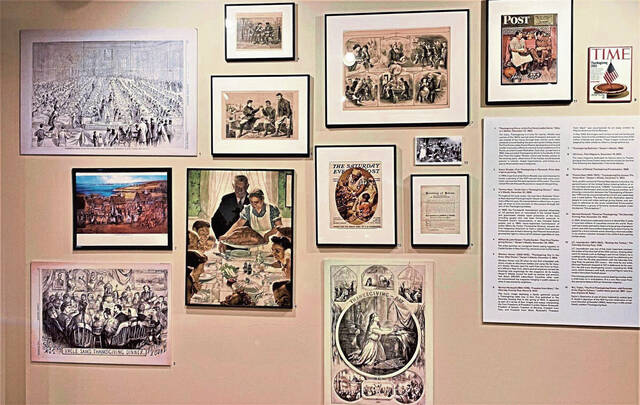

Brief history of Thanksgiving

1621 — Plymouth colonists and the native Wampanoag share an autumn harvest feast today acknowledged as one of the first Thanksgiving celebrations in the colonies.

1789 — President George Washington issued the first Thanksgiving proclamation by the national government of the United States. His successors John Adams and James Madison also designated days of thanks during their presidencies.

1817 — New York became the first of several states to officially adopt an annual Thanksgiving holiday, though each celebrated it on a different day.

1863 — President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation entreating Americans to ask God to care for those affected by the Civil War and to heal the nation’s wounds. He scheduled Thanksgiving for the final Thursday of November, when it was celebrated every year until 1939.

1939 — President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved the holiday up a week in an attempt to spur retail sales during the Great Depression. Those opposed to the change derided it as “Franksgiving.”

1941 — Congress passed a bill solidifying Thanksgiving as the fourth Thursday of November.

Source: history.com

Shirley McMarlin is a Tribune-Review staff writer. You can contact Shirley by email at smcmarlin@triblive.com or via Twitter .

Remove the ads from your TribLIVE reading experience but still support the journalists who create the content with TribLIVE Ad-Free.