A tiny stream — barely more than a ditch, really — trickles past homes in Greensburg’s Northmont neighborhood. Another flows along Ashbaugh Road in Penn Township.

In the 247 years since the founding of Westmoreland County, nobody considered these diminutive waterways significant enough to merit an official name.

Until now.

Such an effort is underway, thanks to a 15-year-old boy from Wellsburg, N.Y., who has made a hobby out of christening unnamed geographical features.

Milo Miller’s first attempt was part of a school project in 2018. He proposed a name for a small stream near his house. He dubbed it Bear Track Creek, after the many bears that roam the area near the New York-Pennsylvania border.

“I was just testing it to see if I could,” Miller said.

The federal Board on Geographic Names approved the request, making his official.

Miller’s been at it ever since, finding unnamed streams, ponds and islands and researching appropriate monikers. He has submitted 18 proposals to the federal board, mostly for streams in and around his hometown. Three have been accepted, so far.

This year, he turned his attention to Westmoreland County.

Local roots

His father grew up in Greensburg, and many of his relatives live in the area. Miller pitched the names Hindman Brook in Penn Township and Wirick Run in Greensburg.

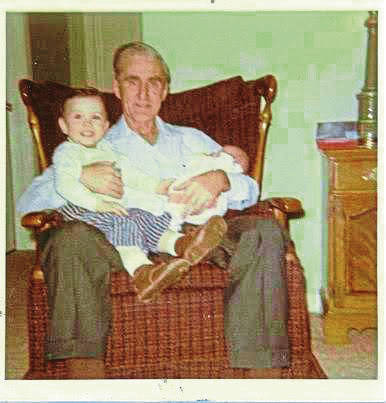

Fred Wirick lived on a farm near the Greensburg creek. He was Miller’s great-great-grandfather, who died in 1950.

Samuel Hindman lived on Ashbaugh Road. He was Wirick’s son-in-law and Miller’s great-grandfather. He died in 2002.

“Samuel Hindman, I’ve heard a lot of stories about him through my family. And the Wirick Run, that was one I mostly just looked back through census records and other forms of local history,” Miller said.

Greensburg city council this week voted in support of the Wirick Run proposal. Penn Township supervisors rejected the name Hindman Brook.

What’s in a name?

While naming geographic features may seem like a job for explorers from centuries past, there are actually many streams and islands in the United States that remain nameless, said Jennifer Runyon, senior researcher for the U.S. Board on Geographic Names.

“You’d be amazed. There’s a lot of unnamed places,” she said.

Anyone can propose to name an unnamed place, or to try to change an existing name, but there are rules. Petitioners must demonstrate why the place in question should have a name, and the suggested name should have a connection to the place, Runyon said. No place can be named for a living person.

“It needs to be a name that will stand the test of time, that has community support, that doesn’t duplicate another name in the area,” she said.

President Benjamin Harrison established the Board on Geographic Names in 1890. It was an era of westward expansion, with settlers seeking a new life and surveyors staking out the frontier. Different groups had different names for the same places, which caused plenty of confusion back in Washington, D.C. The board was tasked with designating an official name for each significant geographic feature.

“Really, nothing has changed. We still meet once a month in (Washington) D.C.,” Runyon said. “Well, right now we’re meeting virtually.”

The board receives dozens of proposals each month. Most requests to christen a previously unnamed feature are approved, while ones to change an existing name are subject to stricter scrutiny, Runyon said.

In either case, local input is important. The board contacts local governments to get their recommendations and learn what the community thinks of a given proposal.

“We don’t have the luxury of going to the community, walking up and down the stream, asking the landowners what they think,” Runyon said. “We don’t want a local citizen coming to us and saying, ‘Wait a minute, I live here, I’ve never heard of this.’”

Local approval

The board forwarded Miller’s requests to Greensburg and Penn Township officials, both of which this week considered the proposals.

Greensburg Mayor Robb Bell grew up near the creek in question, back when it ran through farmers’ fields.

Though he said he has not spoken with Miller, Bell supported the request — but doesn’t think locals will use the new name. The stream may not have a title that appears on any map, but residents have referred to it by an unofficial moniker for longer than he can remember.

“It’s always going to be the Northmont Creek,” he said. “Everyone in town is going to call it that.”

Regardless, council unanimously voted in favor of Miller’s request.

Penn Township supervisors decided not to support the naming request.

“We have been talking about this for several months,” said township Manager Mary Perez. “There was really nothing that raised to the level of a significant contribution to the area from Mr. Hindman,” who was a line worker for West Penn Power.

Once a local government weighs in, naming proposals are sent to the Pennsylvania Geographic Names Authority, then back to the federal Board on Geographic Names, which has final say.

Penn Township’s rejection is probably the end of the Hindman Brook proposal, at least for now. Local input is one of the most important factors the board considers, according to Runyon.

If the new names are approved, they will eventually appear on federal maps, which the U.S. Geological Survey updates every few years, Runyon said.

Rare hobby

Most proposals are sent in by people who have never done it before — and likely never will again, Runyon said.

People like Miller, who submit many proposals, are not unheard of. They also are not common.

“He seems to have made this his project, to find these unnamed tributaries,” Runyon said.

Miller said he enjoys the process and the research, which helps him learn the history of his family and the communities where his chosen streams are located.

“It’s pretty cool,” Miller said. “It takes a lot of work to submit a proposal, so it feels good for it to be accepted.”