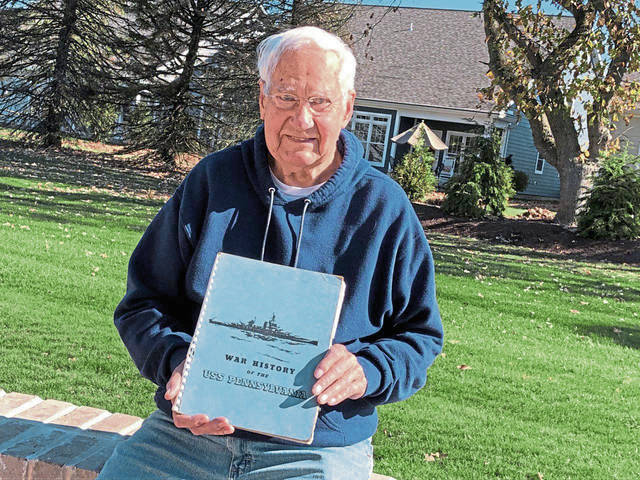

75 years later, memories of World War II, USS Pennsylvania vivid for Greensburg veteran

More than 75 years later, memories of the USS Pennsylvania are still vivid for Bill Kowinski.

The 94-year-old Greensburg man was a sailor aboard the battleship when a Japanese bomber struck it with a torpedo on Aug. 12, 1945, during the Battle of Okinawa in the waning days of World War II.

“I was in my bunk around 8 p.m., trying to get some sleep to go on the midnight watch,” he said. “All of a sudden, there was an explosion and the ship went up and down two times.”

The torpedo ripped a 60-by-38-foot hole in the ship’s hull.

“From that moment on, it was chaos,” said Kowinski, who was 19 at the time.

But it was controlled chaos.

“When you’re young, you have no fear; you don’t know what fear is,” Kowinski said. “You didn’t question orders. You just wanted to do what you could do to save the ship.”

Crew members fell back on their training, pumping water out of the lower compartments and closing hatches to keep others from flooding. Tough decisions had to be made.

“The men closing the hatches could hear sailors knocking to get out,” Kowinski said. “But of course, they never got out.”

Frogmen went over the side to weld a patch, as two sea-going tugboats came alongside to keep the ship from sinking.

There were 2,700 people aboard.

In the aftermath, it was discovered that 20 men died and 10 were injured.

Sturdy ship

The Pennsylvania was the last major U.S. warship damaged during the war. On Aug. 15, the ship received news that the Japanese had surrendered.

A story made the rounds, Kowinski said, that one of the sailors wrote home and said, “We didn’t shoot the plane down, but we ruined the hell out of their torpedo.”

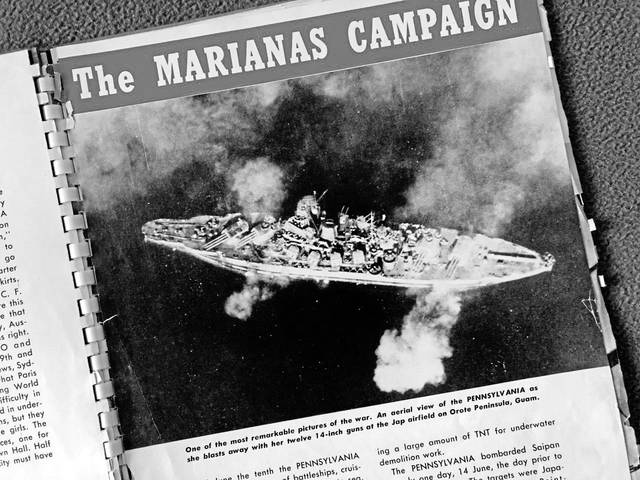

Commissioned in June 1916, the USS Pennsylvania was Battleship No. 38. It was the lead ship of the Navy’s Pennsylvania class of super-dreadnought battleships built in the 1910s.

In 1918, the ship escorted President Woodrow Wilson’s party to France for WWI peace negotiations.

The ship was damaged in drydock during the attack on Pearl Harbor Navy Yard in Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941. After repairs, the Pennsylvania was engaged in operations in the North and South Pacific theaters.

Following the torpedo attack, tugboats escorted the ship to Bremerton, Wash., “and that’s when we got off,” Kowinski said. “Then we went to (the naval training center in) Bainbridge, Md., where I was honorably discharged.”

The Pennsylvania was repaired just enough to make the voyage to Bikini Atoll for the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests in 1946, surviving two blasts.

“Even the atomic bomb couldn’t sink her,” Kowinski said.

The ship was badly contaminated with radioactive fallout, though, and was scuttled off Kwajalein atoll in February 1948.

Life at sea

Kowinski’s journey to the South Pacific began in the village of United in Mt. Pleasant Township. At 17, after his junior year of high school, he enlisted in the Navy “so I could do something for my country.”

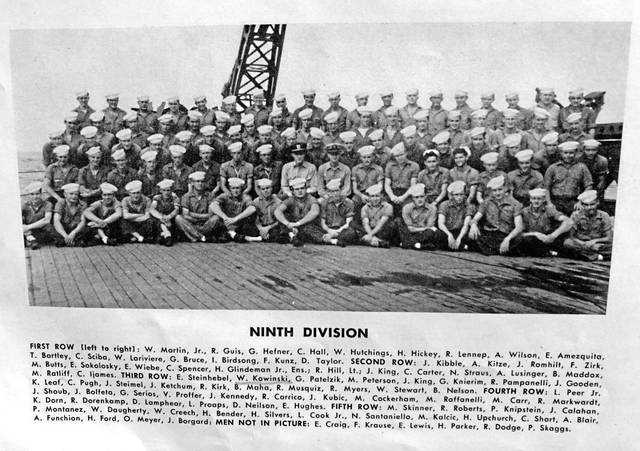

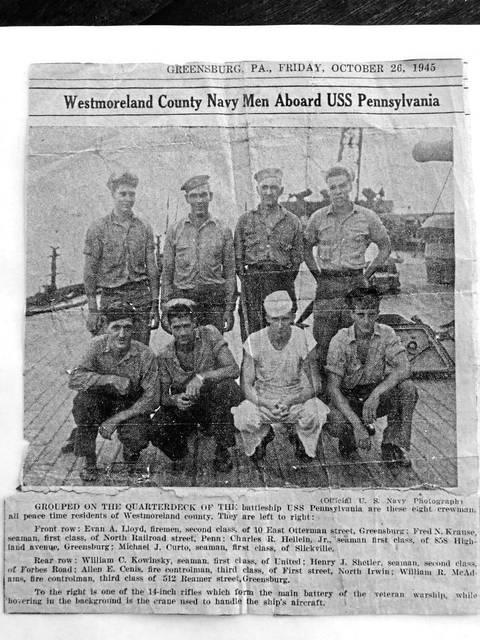

Kowinski trained at Naval Station Great Lakes in Illinois and shipped out to Pearl Harbor in August 1943. He was one of eight sailors from Westmoreland County aboard the Pennsylvania.

“As far as I know, I’m the only one surviving,” he said.

Kowinski saw plenty of fighting in the South Pacific, noting the Pennsylvania fired more ammo than any other ship in that theater. But among the battles were more mundane moments, as daily life went on even in the midst of war.

A lingering sore throat led to a visit with the ship’s doctor, who told Kowinski his tonsils needed to come out. The operation was performed with patient and doctor facing each other while sitting on three-legged stools.

Kowinski opened his mouth and the doctor snipped the first tonsil off.

“The first one wasn’t too bad,” he said. “The second one, I wanted to bite his arm off, because I knew what was coming.”

There was a memorable trip to Australia for R&R.

“We had a band on board, so we radioed in to Sydney and told them we were coming,” Kowinski said. “We asked if we could get some Australian girls to come to a dance, and they did.

“I think every girl in Australia was at that dance.”

And there was a shipmate who went on to fame.

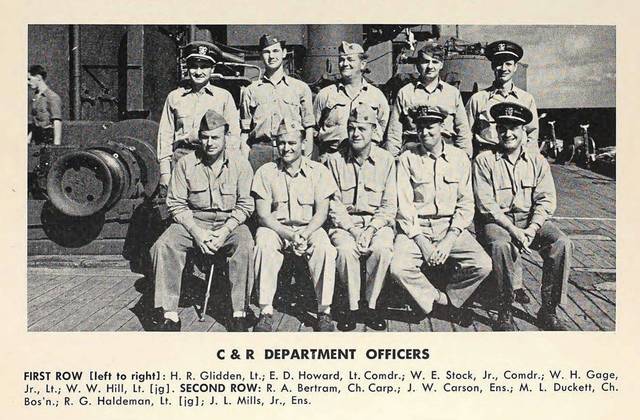

“When Johnny Carson came on board, he would entertain the troops with magic tricks,” Kowinski said. “He did card tricks. He boxed a couple times. He bragged about doing a trick on some admiral.”

The late talk show host was a communications officer who decoded encrypted messages. After the torpedo attack, Kowinski said, “It was Johnny Carson’s job to gather the casualties to be buried at sea.”

Telling the story

After he was discharged, Kowinski returned to Westmoreland County, where he met his future wife, Greensburg native Carmella Pace.

He got his GED and trained in Chicago to be a radio and television repair technician, but never worked in that field. After a short stint at the General Motors plant in Dravosburg, he got a job with the Elliott Co. in Jeannette.

Prior to retiring, he worked in Elliott’s quality assurance department for 36 years.

Kowinski never talked much about his service until the last five years, said his daughter, Carmen Eisaman of Hempfield.

The passing years changed his mind, he said.

“I never thought of telling it before, but I’m going to be 95 (in December),” he said. “Being this old, I thought people should know.

“I volunteered to fight for the people in this country’s freedom.”

Shirley McMarlin is a Tribune-Review staff writer. You can contact Shirley by email at smcmarlin@triblive.com or via Twitter .

Remove the ads from your TribLIVE reading experience but still support the journalists who create the content with TribLIVE Ad-Free.