John F. Mook of Leet dedicated his life to serving his country, community and family.

The former Sewickley police chief and Pittsburgh officer died June 20. He was 83.

Law enforcement was one of his passions.

Mook served in the U.S. Army Military Police in the early 1960s and began his civilian career with Pittsburgh Police in 1965.

He rose through the ranks and became assistant chief of investigations before retiring in 1992.

Mook was not out of work long as he became Sewickley’s top cop that same year. He served the borough for 15 years.

“He’s an all-world human being,” current Sewickley police Chief David Mazza said. “I grew up in the North Side, and he lived two blocks away from me. I’ve known that man since I was a kid. … Chief Mook was responsible for getting me into police work. I owe him a great deal.”

Mazza has been with the Sewickley department since 1996 and was named chief in December 2021.

He started out as a dispatcher under Mook’s leadership while still training at the Allegheny County Police Academy.

“I learned so much from that man that you couldn’t possibly learn in any classroom,” Mazza said. “He was an old-school hard-nosed guy with a soft spot, especially a soft spot for kids and young parents with young kids. … He took care of people the best he could.”

Mazza, 51, found himself of the wrong side of the law as a teen. He got a speeding ticket at 16.

Mook, a former Allegheny County Police Academy instructor, helped Mazza through that time. As a thank you, Mazza attempted to cut his grass.

“He looked at me and he says, ‘I like cutting my own grass,’ and he walked in his house,” Mazza said. “That’s how he was, but he did appreciate it.”

That same year, Mook would help Mazza once again. Both had been training for the Pittsburgh Marathon. Mazza had not registered in time, and Mook had suffered an ankle injury prior to the race. They bonded over their love of running, and Mazza ran in Mook’s stead.

Community-oriented policing is one of the law enforcement efforts Mook instilled in Mazza that continues today.

“His belief was feet on the street,” Mazza said. “He was out in the community walking around all the time. … He was a cop’s cop. He was right there with you. He would never ask you to do something that he wouldn’t do or hasn’t done himself.”

Back at home

Beyond the badge, Mook was a husband, father, grandfather and much more.

“He was a disciplinarian, that’s for sure,” said Mook’s son, Jack David Mook. “His rules were strict. He let us do things. We were allowed to go hang out, but you knew don’t break the law. He was very real about things. He didn’t sugarcoat (and) he didn’t try to protect our feelings. He was always honest and straight forward about this.”

The patriarch worked hard to provide for the family and often worked overtime to “make sure summers were good for us,” the son said.

“Myself and my brother and sister, he would get us involved in things,” Jack Mook said. “School, sports, whatever it was. A lot of camping, fishing trips, traveling.”

Jack would follow in his father’s footsteps joining the Army and later worked for the city police force as a detective. He got a head start on his training.

The father and son would go on surveillance of bookies and bet takers in the 1970s. They never had any contact with suspects during those details.

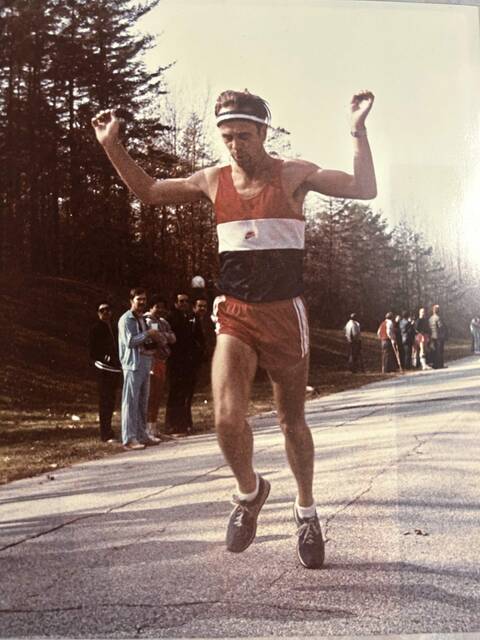

Mook was an avid outdoors man and runner. He competed in many triathlons, marathons and races, including the Pittsburgh, Boston and Marine Corp. marathons — most of which he would finish first in his age group.

He was recognized in Groenoble, France, for placing in the top eight marathon finishers, who worked in law enforcement, of the New York Marathon in 1984. He also carried the torch for the Special Olympics.

Mook often worked out at the family’s gym, Jack’s Boxing Gym, in the North Hills area and supported many young competitors by attending their fights.

“Everything that he did in his life, he did it to the fullest,” said granddaughter Christie Kaelin. “He would fix up fishing rods and bicycles and make sure all the kids were outfitted with bikes and fishing rods. He loved to be outside. He could have lived outside every day.”

Kaelin also recalled going on a lot of family trips and learning the value of a dollar from Mook.

“His big thing is money and being prepared,” she said. “He always instilled in us to save your money and have a good credit score, but as kids you don’t really think about that stuff till you get older.”

Kaelin was tasked with crafting Mook’s eulogy.

He is survived by his wife of 54 years, Jacqueline Mook; daughter Beverly Dimond; sons Ronald Edward and Jack Mook; grandchildren Kaelin, Melanie Mook, Michael Dimond, Donald Dimond, Josh and Jessee Mook; and many other relatives.

Going beyond

There was no funeral for Mook.

He donated his body to Science Care, an organization that offers body donations and cremation services to donors and families at no cost.

Family members said he very adamant about having his remains be used in University of Pittsburgh research. The arrangement was made at least a decade ago.

“He figured whatever they can learn from his body, his remains, he was all for it,” Jack Mook said. “Whatever it would take to help others survive, he was for it.”

A memorial service was planned for July 12 at St. Stephen’s Anglican Church in Sewickley.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital or to Jack’s Boxing Gym for youth development and sponsorship.