Story by JONATHAN D. SILVER

Tribune-Review

Sept. 10, 2023

J. Robert Oppenheimer’s brilliant mind belonged to the atom, his loyalty to the United States, his passion to the New Mexico desert. But the beating heart of the American Prometheus belonged to a woman who grew up in Aspinwall.

Yes, Aspinwall, childhood home of the great physicist’s wife, Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer.

Who could have imagined that the life story of the so-called father of the atomic bomb would be inextricably linked to this placid Pittsburgh suburb, even if only by marriage?

“Of all the places in the world, are you kidding me?” said Dan Martone, the borough engineer.

Viewers of this summer’s movie blockbuster “Oppenheimer” could be forgiven for not knowing the connection.

Listen to TribLive’s Jon Silver and producer Zac Gibson discuss the topic, followed by an author reading of the story by Silver.

The borough isn’t mentioned in the three-hour opus that tracks the theoretical physicist’s frantic race to build the atom bomb – and his fall from grace amid accusations during the 1950s Red Scare that he was a security hazard because of his past Communist associations.

No plaque marks Kitty’s childhood home. Actress Emily Blunt, who plays Oppenheimer’s complicated, polarizing and strong-willed wife, doesn’t make any reference to her Pittsburgh-area past. And even the FBI file on Kitty misidentified where she spent her youth as “Aspenwald.”

One would have to mine dusty, decades-old records — a marriage license for Kitty and her first husband at the Allegheny County Courthouse, land records at the County Office Building in Downtown Pittsburgh, a photograph of the Aspinwall High School Class of 1928 in the basement of the borough building — to turn up anything indicating that the Pittsburgh area fell, by association, within Robert Oppenheimer’s orbit.

Or you could just read the original source material for the movie, the tome “American Prometheus,” to find a passing reference to Aspinwall — tucked into page 155.

The nexus between Pennsylvania and one of the most critical figures of the nuclear era has remained obscure to all but the most diligent scholars, little appreciated and for the most part lost to time.

While some of the region’s links to the dawn of the atomic age stood in plain view — Westinghouse, for instance, built the world’s first commercial nuclear power plant in Shippingport and designed the reactor for the first nuclear submarine — others were invisible like gravity.

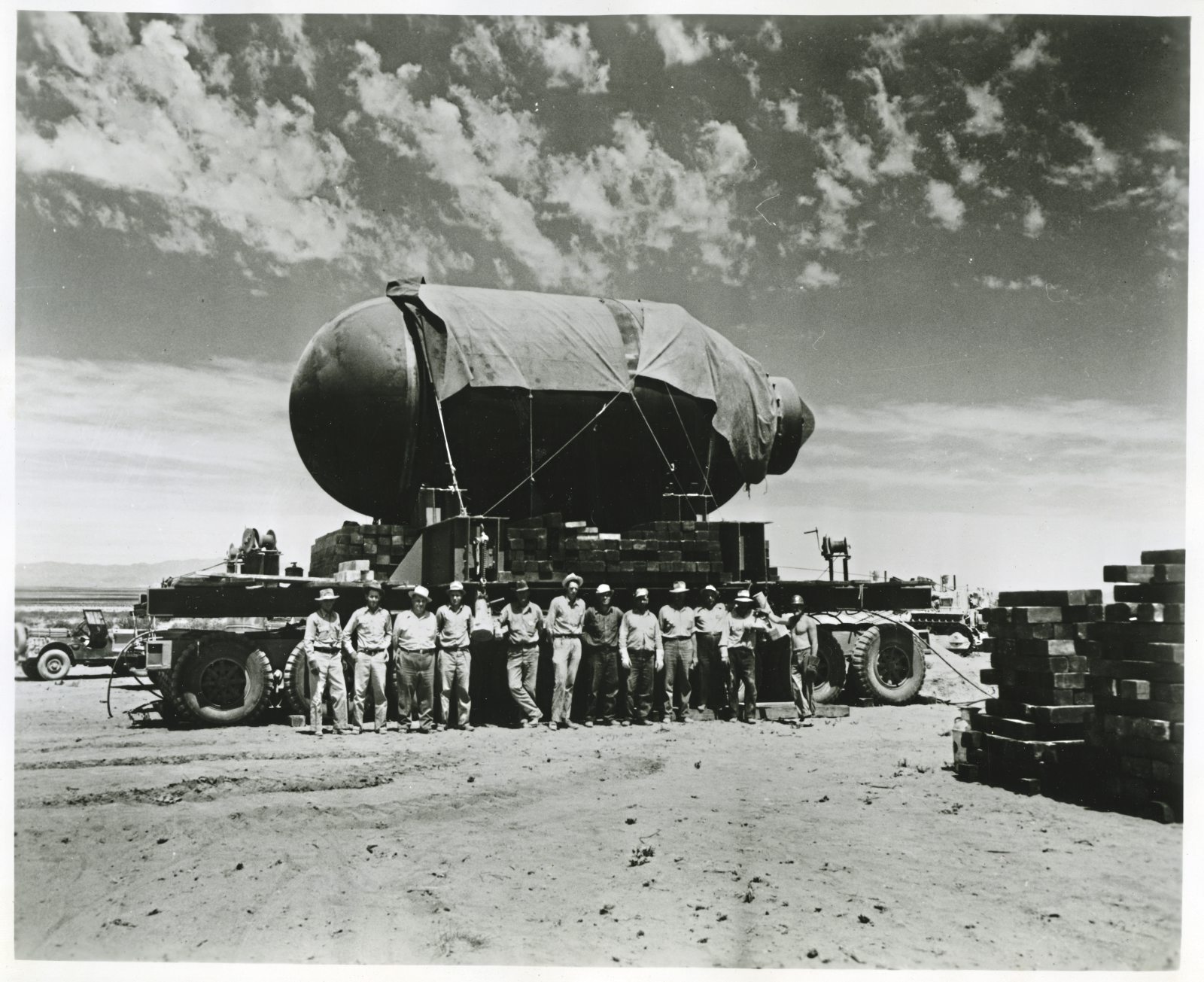

The promise — and peril — of the power of the atom cast long shadows over Pennsylvania. They stretched from Forest Hills, home of the now-toppled Westinghouse atom smasher, to Shippingport; from Pittsburgh, original home of the Eichleay Engineering Corp., to the remote New Mexican desert, where Eichleay workers transported a 214-ton metal canister nicknamed “Jumbo” to the atom bomb test side codenamed “Trinity”; from Aspinwall to West Deer, where the Kratz family constructed a backyard nuclear fallout shelter and amassed an impressive collection of atomic-age ephemera.

Throughout Western Pennsylvania, scientists labored to unlock the mysteries of the quantum universe, engineers harnessed the atom’s energy, and families learned to fear a nightmare scenario of annihilation in a radioactive mushroom cloud.

And in tiny Aspinwall, a little girl who was born in Germany could not possibly conceive that one day she would occupy a front-row seat to history.

For years, Kitty Oppenheimer stood by her world-famous husband. She sweated it out in Los Alamos, endured his devotion to former lover Jean Tatlock, grappled with her own problems with alcohol, and stuck up for him in 1954 when the U.S. government turned on him, humiliating Oppenheimer and declaring him a security hazard.

Kai Bird, who with Martin J. Sherwin co-authored the Pulitzer Prize-winning “American Prometheus,” the book on which the movie is based, described her as complex and mercurial.

“Kitty is a very central figure in Oppenheimer’s life. She was quite a colorful character in her own right,” Bird told the Tribune-Review. “She comes across as a very strong personality and a little tortured with her own ambitions. I mean tortured because she ended up going to Los Alamos and being the wife and mother and found those roles to be limiting and tough for her to carry out.”

Born Katherine Puening, Kitty made her entrance to the world in August 1910. The daughter of Franz Puening and the former Kaethe Vissering, she spent her infancy in Germany’s North Rhine-Westphalia state.

In 1912, Franz set out alone for the U.S. to seek his fortune while in his early 30s. Standing 5 feet 6 inches, with brown hair and brown eyes, Franz would have made the passage in less than a fortnight on the ocean liner SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, named after Germany’s first emperor. Franz’s wife and blue-eyed daughter would steam across the Atlantic and join him the next year.

Franz had already tasted success, according to Shirley Streshinsky and Patricia Klaus, authors of “An Atomic Love Story,” a book about Oppenheimer and three women, including Kitty, who loved him. He had invented a new type of blast furnace, they wrote, “which he felt would be in demand in the Iron Belt of the United States.”

For a time, Franz worked as a chemical engineer in Chicago. But in 1921, a year before Oppenheimer enrolled at Harvard, his future father-in-law surfaced in Allegheny County. That year, Puening made the first of numerous land purchases in O’Hara. His buying spree would last until 1928.

Deed books at the County Office Building show seven discrete transactions by Herr Puening of lots on and near Delafield Road. Prices ranged from $600 to $4,000, or between about $10,000 and $70,000 today.

What prompted Puening to leave Chicago for Allegheny County is unknown. But by 1922, Puening made it clear that he was in the U.S. to stay, becoming a naturalized citizen at Pittsburgh’s federal courthouse, then at Fourth Avenue and Smithfield Street. A contemporary city directory listed him as a chemical engineer with Koppers Co. and living in Aspinwall.

By then the family was well integrated into Pittsburgh cultural circles. That year, one of the Puening women — likely Kitty — took part in a piano recital of junior students of the Pittsburgh Musical Institute on Bellefield Avenue. A June 7, 1922 edition of The Pitt Weekly listed the performers. Among them: Katherine Puening, playing the cheerful Elfin Dance by German composer Adolf Jensen.

Kitty’s mother had high aspirations for her daughter. “…[E]ven if the Puenings didn’t socialize with the Carnegies, Fricks, or Mellons in Pittsburgh, Kaethe would see to it that her only child would know how to navigate in their world,” according to “An Atomic Love Story.”

Kitty became a proficient horseback rider, the authors wrote, noting that “Aspinwall had its own riding trails.” Years later, this skill would help enthrall Oppenheimer, himself an excellent horseman, as they rode through the Sangre de Cristo mountains in New Mexico.

While the Puenings provided their only child with a comfortable upbringing in Aspinwall, all was not easy.

“As German immigrants,” they wrote, “the Puenings sometimes had a difficult time in Pittsburgh during World War I. As an enemy alien, Franz Puening was placed under surveillance by local authorities, and even young Kitty had a hard time with neighborhood kids.”

<!–

–>

Kitty had to learn English in America. By the time she was a teenager, her spirited streak was on display with her classmates.

“She was wild as hell in high school,” a friend of Kitty’s told Bird and Sherwin.

Kitty and her family lived on Delafield Road through the 1920s. Their “capacious home” became what authors Streshinksy and Klaus called a “headquarters for the circle that revolved around Kitty.” She was “bright, outspoken, daring,” they wrote – and attractive to men. A high school boyfriend described her as “intellectually superior” and said that she “had moved decidedly to the political left in her senior year.”

By 1930, census records show, the Puenings had moved to Hampton Road in O’Hara, a short street which is today part of Fox Chapel.

The census doesn’t reflect a street number, so it’s not clear whether the Hampton Road house still exists. But clearly Kitty’s family was doing well.

The home, which the family owned, was valued at $26,000 — nearly a half-million dollars today – and the Puenings had a servant, a young woman newly arrived from Germany.

In 1928, right after graduation from Aspinwall High School, Kitty enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh. She wouldn’t complete her degree there, though.

Instead, wrote Bird and Sherwin, Kitty embarked on a “checkered college career,” returning to Europe to study in Germany and France, but mostly spending time as a flâneuse lounging in Parisian cafes.

She would eventually find her way back to the U.S. educational system, graduating with honors in 1939 from the University of Pennsylvania as a botany major.

One notable event took place in that period of Kitty’s life: She acquired a husband.

On Christmas Eve in 1932, Kitty applied for a marriage license in Allegheny County with Frank W. Ramseyer, a musician and Boston native five years her senior. They were wed two days later. But Bird and Sherwin say that the marriage, which they described as impulsive, quickly soured.

“Several months into the marriage, Kitty found her husband’s diary — he kept it in mirror writing — and learned that he was both a drug addict and a homosexual,” they wrote.

Before a year was out, according to the authors, Kitty began studying biology at the University of Wisconsin, and the marriage was annulled in that state.

But romance for Kitty would soon blossom again in Pittsburgh. Ten days after the annulment, according to the authors, Kitty was home for a New Year’s Eve party when she met Joe Dallet, a sophisticated German-Jewish Communist who could play piano and speak fluent French. Despite a privileged upbringing, Dallet abandoned his moneyed roots and worked blue-collar jobs as a longshoreman, coal miner and union organizer following his political awakening, Bird and Sherwin wrote.

Kitty fell in love with him. They married six weeks later, and Kitty joined him in Youngstown, Ohio. It didn’t take long before she was handing out Communist literature on the streets of Youngstown, according to the authors.

But by the end of 1937, Kitty was a war widow: Dallet had gone to Spain to fight the fascists during the Spanish Civil War and was killed in battle. The Puenings had moved to London, according to “An Atomic Love Story.” Aspinwall was no longer home.

Fast forward two years to a garden party in Pasadena, Calif., a world away from Aspinwall. It was there that Kitty, 29, first laid eyes on Robert Oppenheimer.

The physicist had just broken up with Jean Tatlock, his troubled occasional lover, portrayed on screen by actress Florence Pugh. And Kitty? She was unhappily married to her third husband, a British physician named Richard Harrison, who had moved to Pasadena to practice medicine. Armed with her botany degree from the University of Pennsylvania, Kitty followed him.

When Kitty met Oppenheimer, she was “immediately mesmerized,” wrote Bird and Sherwin. Their affair began soon after.

“She was very attractive,” a physician who taught at Berkeley told the authors. “She was tiny, skinny as a rail, just like [Oppenheimer] was. They’d give each other a fond kiss and go their separate ways. Robert always had that porkpie hat on.”

Bird and Sherwin describe Kitty as petite, attractive and vivacious. The botany major cultivated orchids, they wrote.

Streshinsky and Klaus painted this portrait of Kitty: “small and vivid, not beautiful in any usual way, but engaging and confident. Her eyes were dark and expressive and she laughed easily – there was nothing coy or timid about her. She was the kind of woman whose appeal could never be explained by a photograph.”

After spending two months with Oppenheimer at his New Mexico ranch in 1940, the physicist himself telephoned her husband to break some big news in what would have been an awkward conversation for most people: Kitty was pregnant.

That November, the Oppenheimers were married. Robert would become Kitty’s last husband, and Kitty would become the revered scientist’s one and only wife.

“She was a sort of mercurial personality and mercurial in her relationship with Oppenheimer. She was obviously quite devoted to him and in love,” Bird said. “Likewise, Oppenheimer stuck by her all those decades till the day he died. She could be a trial.”

In the movie, Blunt portrays Kitty, a onetime Communist, as sharp-tongued, intelligent and staunch in defending Oppenheimer against the government’s attacks in 1954.

“We make a point of describing her role in the trial … as an extraordinary performance where Oppenheimer himself seems passive and unable to defend himself,” Bird said. “Kitty is just the opposite and is able to parry the questions of the prosecutor and to make fun of them and to deflect his interrogation. And she did it with wit. It was further evidence of how clever a woman she was.”

Now, nearly a century after Kitty graduated from Aspinwall High School, Martone, the borough engineer, has become fascinated by her story. He’s made a point of trying to track down her childhood home and believes that once he does, it should be memorialized.

Bird believes that Kitty would be a worthwhile figure to remember. He noted that Kitty cut an unusual path for a woman in the 1930s, traveling all over Europe, joining the Communist Party and shrugging off the trappings of her upbringing. Opinionated, ambitious and steadfast, Kitty was an early feminist, desired a career and likely struggled through postpartum depression, according to the author.

“Though she grew up in privileged circumstances in Pittsburgh, she went to Youngstown, Ohio, with her new husband, Joe Dallet, spent four years living in very straitened circumstances passing out leaflets at factory doors,” Bird said. “She was an incredibly passionate figure and, I should think, an interesting role model for women today.”

On Feb. 10, 1945, with the Oppenheimers living in Los Alamos and the Manhattan Project in full swing, a branch of the U.S. War Department drafted a document that would forever link a Pittsburgh company to the covert effort to build the atom bomb.

Stamped “SECRET,” the typed title was deliberately vague: “Specifications for transporting and placing government-owned vessel.”

Whichever cautious military men dreamed up that heading wanted to shroud the project’s true purpose.

The “vessel” was a 214-ton metal canister nicknamed “Jumbo.” As heavy as a blue whale, it measured almost 27 feet long, about 12 feet in diameter and had steel walls more than 15 inches thick. The Army was looking for a company to do something it couldn’t: move the thermos-shaped unit about 30 miles across unpaved desert to a site known as Trinity.

Enter the Eichleay Engineering Corp. of Pittsburgh.

A family-run enterprise, Eichleay specialized in transporting incredibly heavy objects — entire office buildings, the gargantuan pipes installed in the Hoover Dam and the whole of St. Nicholas Church in Oakland, to name a few.

In 1926, according to The House Movers, a company history written by John W. Eichleay Jr., the founder’s great-grandson, Eichleay’s chief engineer summed up his team’s can-do spirit this way: “They don’t build them too big for us to move.”

Nearly 20 years later, Eichleay once again proved that motto to be true.

So what was Jumbo?

To understand, one first needs to appreciate the immense challenge facing Manhattan Project scientists in creating weapons-grade plutonium and uranium in sufficient quantities to power a bomb.

“Oppenheimer” cleverly captured this painful creep of production. Actor Cillian Murphy, portraying the theoretical physicist, is shown month after month dropping marbles into glass bowls, representing the excruciatingly slow refinement of the critical radioactive isotopes. Eventually, the bowls were filled, and America had its nuclear catalyst.

As Los Alamos engineer Jonathan Morgan put it in a 2021 paper for the journal Nuclear Technology, the extremely limited supply of plutonium made “gold look rather pedestrian.”

So incredibly valuable to the U.S. war effort was the plutonium, Morgan wrote, that “concern was raised about the possibility of wasting the precious plutonium in a fizzle, or dud…”

The bomb at Trinity was meant to be detonated through two explosions: first, TNT, followed a fraction of a second later by the nuclear material.

“The scientists were sure the TNT would explode, but were initially unsure of the plutonium,” according to the U.S. Army. “If the chain reaction failed to occur, the TNT would blow the very rare and dangerous plutonium all over the countryside.”

And so was born the idea for Jumbo — a huge metal can to hold the test bomb, code-named Gadget, and allow the isotopes to be salvaged if the weapon flopped.

“The physicists were afraid that if the reaction did not go the way they hoped it would – an enormous explosion – that they would lose all this material, and that would put the whole race to have a super bomb back months, if not years,” Eichleay, 77, of Shadyside, said.

“So this thing was sort of a failsafe mechanism that they could retrieve the valuable radioactive material if it didn’t work.”

Just as scientists and engineers were in uncharted territory trying to build a nuclear bomb, they were also pioneering a way to contain the massive TNT blast.

First, they considered a huge steel sphere. Only three companies in the U.S. could make such a unit, according to Morgan. All were in Pennsylvania: General Engineering and Foundry Co. and Jones & Laughlin in Pittsburgh, and Bethlehem Steel.

But various concerns led Oppenheimer to reconsider that design. Eventually they settled on what became Jumbo. Tapped to build it: Babcock & Wilcox, an Akron-area company.

Babcock & Wilcox had no idea what Jumbo was for. Neither did Eichleay, nor any of the other Pittsburgh-area companies working in ignorance on different facets of the war effort, according to Leslie Przybylek, senior curator at the Senator John Heinz History Center.

“No one knew what they were doing,” Przybylek said. “They were only told so much.”

It’s not surprising that Western Pennsylvania played a role. Not only was Pittsburgh a research and technology hub with Westinghouse, Mellon Institute and Carnegie Tech, but the region also had companies that turned out electronic equipment, scientific instruments, precision metal parts and enamel components. A trucking firm, W.J. Dillner Transfer Co., was the sole hauler of bomb materials from Westinghouse to Oak Ridge, Tenn., where scientists were enriching uranium, according to Przybylek.

Secrecy was paramount. Top brass in the military wanted to compartmentalize information to make sure one hand didn’t know what the other was doing.

In “Oppenheimer,” Matt Damon plays Gen. Leslie R. Groves, the ultra-cautious impresario of the Manhattan Project.

Groves feared “that randomly dropped phrases, bits of knowledge, and names or places might fall into the hands of some centralized enemy spy network, where it might then enable reconstruction of the project,” according to the Atomic Heritage Foundation.

So paramount was security in building Jumbo that the government used “obscure procurement methods so that items could not be traced back to the project,” Morgan wrote.

To underscore the secrecy of the project, the first page of the War Department proposal warned that anyone who publicized the information it contained could be prosecuted as disloyal to the U.S. war effort under the Espionage Act.

It was difficult to manage a crew from Pittsburgh in the desert, with the nearest civilization outside of the Los Alamos base 35 miles away in Socorro, N.M., according to Eichleay.

<!–

–>

“They knew this was a big war effort, but they didn’t know what they were doing,” he said. “They’d work hard in the desert all day and go into Socorro or someplace like that and knock back beers and talk about what they were doing in this hellhole, this hot place.”

But people were listening.

“The people they would be talking to would be FBI agents,” Eichleay said. “Dad had a hard time maintaining the crew. … They lost about three or four of them because of their loose lips.”

Chatterboxes would be put on the next train back to Pittsburgh, he said.

Pennsylvania continued to play a central role in Jumbo’s construction, according to Morgan. Midvale Steel Corp. in Philadelphia contributed a key nozzle. And when only partially completed, the entire unit was shipped to Mesta Machine Co. in West Homestead to be worked on a large lathe.

Once Jumbo was finished, it needed to be moved. The Army was on a strict timetable. It wanted the task finished by June 15, 1945.

It soon became clear why. One month and one day later, the world’s first atomic bomb was successfully detonated at the White Sands Missile Range.

A Mercer County manufacturer of railroad equipment — Greenville Steel Car Co. — made the railcar used to take Jumbo from Ohio to the desert, Morgan wrote.

<!–

–>

The next step: hauling it from the railroad siding in Pope, N.M., to Trinity. Babcock & Wilcox suggested Eichleay, whose experience moving the Hoover Dam pipes had prepared it for Jumbo.

An Erie County company, Rogers Brothers Corp., built the 64-wheel chassis that was used. Tractors were hooked up to the trailer, and the contraption towed Jumbo across the white gypsum sand dunes of the Chihuahuan Desert.

But by then, after all that time, effort and money, the scientists had decided they weren’t going to use Jumbo after all.

Morgan noted that although major concerns about the Gadget lingered mere days before the Trinity test, the scientists months earlier had ruled out encasing the bomb, worried that doing so would block access to critical test data if the nuclear explosion worked.

That created a new problem.

“What was Gen. Groves going to do with this enormous thermos bottle that they had paid tens of millions of dollars for?” Eichleay said. “That was a lot of money back then.”

The solution: rig it up in a giant steel tower a half-mile away to see if it could withstand the blast.

“I think that’s why my father was actually out on the site,” Eichleay said. “This was a significant change order in the scope of their work, and he had to go out here and talk to the Army engineers and get an idea what they wanted.”

So they hoisted Jumbo horizontally, flipped it to the vertical position, and lowered it back to the desert floor to await the detonation.

Three observation points were set up, each 5.68 miles north, south and west of ground zero, according to the government records. Their code names: Able, Baker — and Pittsburgh.

Just before 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945, Gadget exploded in a blinding white flash.

Success.

Heat like the sun flooded Trinity. Particles of desert sand fused into green glass. Windows broke 120 miles away. A mushroom cloud bloomed nearly 40,000 feet skyward. The tower that held the Gadget was vaporized, and the one surrounding Jumbo was destroyed.

But Jumbo survived unscathed.

The big jug soon came to an ignominious end. In 1946, eight unusable 500-pound bombs were lowered into the canister.

When the bombs exploded, they blew the ends off Jumbo. Despite surviving a nuclear blast, the steel container couldn’t contend with less powerful explosives, since they were placed in the bottom of the unit touching the vessel wall — not in the middle as per the design. Metal fragments whizzed through the air, landing nearly a mile away.

Morgan theorized that Jumbo was used for unexploded ordnance to justify its construction in case auditors poked around on the $12 million project — what would these days be a $200 million boondoggle.

Today, the remnants of Jumbo remain at the entrance to ground zero. And Eichleay remains modest about the role his family company played in the war effort.

To say that his father was part of the Manhattan Project, he said, would be “gilding the lily.”

But when asked how he feels about the work that went into transporting Jumbo, Eichleay summed it up with one word: “Pride.”

If anyone was prepared to survive a nuclear holocaust, it was Edgar Kratz.

He knew that the first warning of incoming nukes might be the civil defense alert signal: a loud, steady blast for three to five minutes.

That would cue Edgar and his wife, Marian, to spring into action. They would round up the girls, Bev and Millie, tune the AM radio to the Conelrad emergency broadcast system and shut off appliances and utilities.

Then they would wait, straining to hear the most chilling sound imaginable: the take-cover signal. Three short blasts shredding the air over three minutes.

In that nightmare scenario, it would be time to go to the fallout shelter — immediately.

For the Kratzes, that would mean the shortest of trips: safety was only as far as the backyard.

They might have been one of the few families in West Deer in the 1950s — maybe one of the few in Western Pennsylvania — to have their own fallout shelter.

Made of concrete block slathered with tar and a poured concrete roof, the structure had a hand-crank mechanism to draw in fresh air through a pipe topped with a mesh filter. The Kratz family fallout shelter was a sign of the times — and the price of progress made by the Manhattan Project.

Kratz, a crane operator at the old Pittsburgh Pipe and Coupling Co., had built the bunker into a hillside in West Deer, covering it with sod. He had constructed his house himself, so why not a sturdy refuge for his family?

To enter the shelter today is a surreal experience. Or as current homeowner Shawn Koschik says, it’s like entering a time capsule.

The shelter’s entrance is roughly 50 feet from the back of the house, hidden but for a black metal air pipe sticking up out of the ground. Dug into a hillock overlooking Deer Creek, the entrance is a weathered metal door set at an angle into the back of the hill.

Big, black spiders have made their homes in the dark, dank shelter, moist despite Kratz’s attempt at waterproofing.

A fragile set of nine wooden steps — eight now since a contractor recently broke one while having a look around — descends roughly seven feet into the darkness, bringing visitors to a hallway wide enough for only one person. A light switch and a bulb no longer work.

Several paces down an oppressive 8-foot-long hallway, a left turn brings you into the cramped living quarters. It’s roughly a square, 8 feet by 8 feet, and less than 7 feet tall. The single, wooden bunk bed — the girls were warned that the family would have to sleep in shifts — has long since moldered, exposing nine glass jugs on the floor that were meant to be the water supply.

A crude chemical toilet is tucked into a corner with a pipe running from it. A few bottles of old cleaning supplies remain.

Kratz’s daughters don’t know exactly how he got it in his head to build a fallout shelter.

Maybe it was the war. Kratz served in the Navy during World War II.

Though Bev Sheirer, Kratz’s eldest daughter, said her father never saw combat, he knew what the bomb could do. By the time he came home from the war, everyone did. The world now lived under the shadow of what Oppenheimer and his fellow scientists had created.

“He was always kind of a nervous fellow. He always bit his nails,” recalled younger daughter Millie Sass, 76, of Pittsburgh’s South Oakland neighborhood. “I guess seeing the war, he understood what war could bring and how disaster could be so much worse with more modern technology.”

In hindsight decades later, the sisters valued his effort.

“I thought it was pretty neat to say you had a bomb shelter, and I appreciate that Dad thought enough of his family to protect them like that, even though I’m sure there was ridicule from everybody,” said Sheirer, 79, of Tidioute in Warren County.

Sheirer, born two years before the atom bomb was dropped, wasn’t bothered by the shelter. She and her classmates were already doing civil defense drills in school, hiding under their desks. She felt relieved to know that if the unimaginable happened, she had somewhere to hide.

“They had nowhere to go,” she said, “and I had a bomb shelter.”

Mechanically inclined, Kratz could often be found sitting at the kitchen table poring over the latest issue of the DIY magazine Popular Mechanics. Sheirer thinks her father might have come across plans for a fallout shelter in one of the editions.

The bunker would have fit right in with Kratz’s concerns about a nuclear war and his meetings at Deer Creek Church with neighbors as part of the West Deer Township Survival Unit No. 2.

They seemed to be following the slogan “Alert today — alive tomorrow” — popularized on posters distributed by the Federal Civil Defense Administration, established in 1951 under President Harry Truman.

A typed piece of paper in Kratz’s possession addressed his neighbors and made clear the stakes facing the group.

“As you know several men have been asked to form and prepare a survival unit in our immediate area which has been done, and we have been in touch with you encouraging you to be prepared,” it stated.

“It is our prayer that what we are asking you to consider may never have to be put into practice. However, in case of nuclear attack it is our concern that this area be as well prepared as possible to meet such an emergency.”

The Kratzes did their part. Both husband and wife earned certificates by completing a 12-hour civil defense adult education course through the state Department of Public Instruction.

Kratz stockpiled material about surviving atomic Armageddon. He had hand-drawn maps of West Deer showing area roads and marked with concentric circles and the locations of neighbors. He kept diagrams of “typical atomic bomb bursts.” He filed away charts of the effects of different levels of radiation exposure.

No doctor on hand in the shelter? No problem. Just consult the booklet “Venipuncture and intravenous procedures.” Need to know how to read your Geiger counter? Peruse the “Handbook for radiological monitors.” How about instructions on helping an infant take a first breath or cutting the umbilical cord? There was a document for that: “Bomb born babies.”

“Whenever a catastrophe or major disaster hits a civilian population, babies arrive in large numbers, prematurely, rapidly and without much ceremony,” it said. “As he cries, hold him up where the mother can see him. Tell her, with all the enthusiasm you can muster, that he is a beautiful baby.”

Kratz also collected a wide array of guides. They were pamphlets of sober title, a compendium worthy of a library shelf: “Family food stockpile for survival.” “Soil, crops, and fallout from nuclear attack.” “Radioactive fallout on the farm.” “Before disaster strikes…what to do now about emergency sanitation at home.”

A hard worker and inveterate perfectionist, Kratz would spend nights, weekends — even times when others would be at church — constructing his fallout shelter.

Sheirer remembers her father toiling. When Kratz poured a concrete slab, he let the family’s two black cats, Ike and Mike, adorn it with their paw prints. He ran electricity to it from the house.

It was tight in the shelter, no wasted space. Everything fit just right.

“You had a bucket at the foot of the beds with this kind of wall, I guess there was a curtain. That was your toilet,” Sheirer recalled.

The girls weren’t allowed to goof around down there.

“It was not a play place,” Sass said. “It was a serious endeavor.”

Having grown up with the shelter, the sisters didn’t regard it as something unusual. It was just a part of their life. But they had questions and concerns.

Coming from a big family all over the nearby farmland, the girls wondered what would happen to their favorite cousins if an attack came. Could they save them?

“No,” their father would say, according to Sheirer. “There can only be four people in there.”

That begged other questions.

What about their two dogs?

How would they get mattresses and food down there in an emergency since Kratz hadn’t thoroughly stocked the shelter?

And if bombs were dropped, how would they ward off neighbors desperate to save themselves?

“It wasn’t a secret. I don’t know how he thought he was going to keep everybody out and only let the four of us in. We did no drills. There were no guns or anything to protect ourselves.” Sheirer said.

There was something else that gnawed at Sheirer.

“I could never understand how we were going to be safe in there, how long would you have to be in there,” she said. “You couldn’t have enough food in there to survive for more than a week maybe. It never made any sense to me that you could live underground and when you came out everybody would be dead.”

Over the years, as the imminent menace faded, the Kratzes began using the shelter as a root cellar.

Edgar Kratz died in 1985. A few years after Marian’s death in 2012, Sass was cleaning out the house when she came across a big box in the basement rafters. It was still sealed.

To her surprise, it contained two gas masks, a Geiger counter and a dosimeter.

She called the Heinz History Center.

“I think I have something you might be interested in,” she told the museum.

Jonathan D. Silver is a Tribune-Review staff writer. You can contact Jonathan at jsilver@triblive.com.