George Nicholas still insists he acted in self-defense nearly 35 years ago when he shot and paralyzed the stranger in the middle of the night.

It was Nov. 30, 1989, and Nicholas thought a man he’d argued with over a traffic dispute was attacking him with a shotgun in Pittsburgh’s Brookline neighborhood.

Nicholas, 31, retrieved a gun from his car. He shot the man twice.

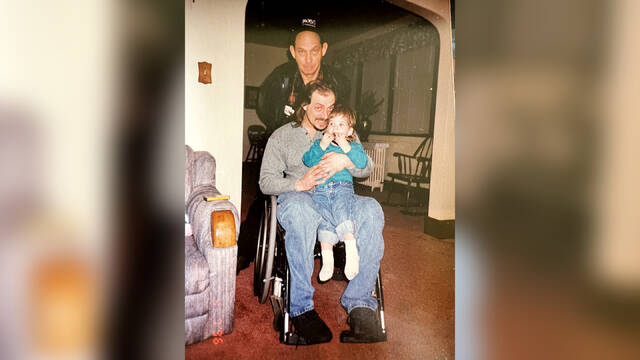

John E. Murray III survived but never walked again. He was 24 years old.

As details from the early-morning encounter emerged, it turned out the shotgun wasn’t a firearm at all. It was a bumper jack that Murray had gotten out of the trunk after his car broke down, his father, John E. Murray Jr., said.

Murray denies that his son was the aggressor.

Whatever the circumstances from that night long ago, they don’t change that Nicholas is full of regret and Murray is bitter.

“I always felt very sad that I hurt another human being,” Nicholas, 66, said recently.

Murray, 83, is unmoved.

“This makes me disgusted,” he said during an interview on his front porch last week. “He ruined my kid’s life.”

Now, decades after Nicholas walked out of prison, a case that seemed over and done might not be over after all.

This past April, Murray died of sepsis at age 59 in his South Side apartment. Last month, authorities ruled the death a homicide.

Now, the Allegheny County district attorney is weighing whether to charge Nicholas anew.

Murray’s father likes the idea.

“Stick his ass in jail for another 10 years,” Murray said.

‘He just kept coming’

When Nicholas and a buddy left the old Tom’s Diner on West Liberty Avenue after 3 a.m., he said, Murray was heading out at the same time.

The two didn’t know each other. But Nicholas claimed that Murray had been glaring at him all night.

As Nicholas went to drive off, he said Murray tore out in front of him, forcing him to slam on his brakes.

Nicholas said his friend hit the dashboard.

Nicholas got out, and he and Murray argued.

But then, he said, Murray got out, too, popped his trunk and emerged with what looked like a shotgun.

Murray came at him screaming, the weapon raised in the air, Nicholas claimed.

Nicholas grabbed his wife’s revolver, a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson, from the car, according to court papers. He said he hid behind his door and fired a warning shot.

“He just kept coming,” Nicholas told TribLive. “I thought he was going to shoot me in the face.”

Nicholas said he aimed at Murray and fired.

“He wasn’t stopping,” Nicholas said. “I shot again.”

Then he fled.

“I should have stayed there,” Nicholas said. “I wasn’t sure (if) they’d lock me up and throw away the key.”

Nicholas went home to Baldwin Borough, to his wife and son, he said, to tell them what had happened.

He hugged them goodbye, he said, and went to turn himself — and the gun — in at the Baldwin police department.

A Yellow Cab driver, who had been parked in the 500 block of Brookline Boulevard at the time of the shooting, told police he heard the gunfire.

When officers arrived, they found Murray, who had been shot twice in the chest.

A bumper jack was on the ground next to him.

A mistrial, then a plea

Pittsburgh police charged Nicholas with aggravated assault, reckless endangerment and two firearms counts.

The case went to trial in April 1991, but the jury couldn’t reach a verdict.

A mistrial was declared, and the DA’s office made plans to retry the case.

Nicholas continued to maintain that he fired in self-defense.

But he said he couldn’t bear the thought of watching Murray being jostled around in his wheelchair to get on the witness stand all over again.

So he pleaded guilty.

Nicholas said he had hoped to apologize, but when he tried to in court, Murray wasn’t interested. The judge chastised Nicholas for interacting with the victim.

When it came time for sentencing, Murray didn’t attend.

Nicholas went to prison, serving nearly three years.

“I want his family to know I’m very sorry this happened in the first place,” Nicholas said. “It was over stupid stuff.”

‘He was so angry’

Murray’s father had been out with friends at a dance the night of the shooting. They returned to his house.

At some point early that morning, the phone rang. One of his friends answered.

The police told her to get Murray to what was then Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh. His son had been shot, they said. He was in critical condition.

Murray remembered how calm and collected his friend was when she broke the news. She was a nurse at Mercy.

For several hours, Murray wasn’t allowed to see his son.

When he finally got into the room, Murray said, he was overwhelmed by the sight of so many wires and tubes.

“It was miserable.”

But Murray’s son hung on. After a lengthy stay at the hospital, he was released to a rehabilitation facility in Harmar, where he remained for months.

“He was angry,” his dad said. “His whole life was screwed up.”

Eventually, his son got an apartment on Sarah Street on the South Side.

“It wasn’t easy,” Murray said.

Murray remembers the trial. He discounted Nicholas’ claim of self-defense and said the man shot his son simply because he was angry.

“My kid didn’t have a (shotgun). They all lied,” he said. “The guy should have stayed in his car.”

Murray thinks Nicholas’ sentence, capped at five years, wasn’t long enough.

Before the shooting, Murray worked with his son in construction and as a carpenter. The young man had also gotten his on-air license from the Columbia Broadcasting School.

“He was a good kid, a good worker,” his dad said.

But, after the shooting, his son never worked again.

Over the years, Murray bought his son four cars outfitted with hand controls so he could drive. He later built a ramp so his son could get into his apartment on his own.

Murray pitched in with spending money — including for a trip to London his son won in a radio contest. He would buy live crickets for his son’s two pet tarantulas.

In the months before John Murray III died, he was hospitalized.

By March, he was discharged home with a do not resuscitate order. He wanted only to be kept comfortable.

Double jeopardy?

Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala Jr. said he hasn’t decided whether to charge Nicholas with homicide.

He and his prosecutors will have to determine whether they can tie Murray’s death to the shooting.

Sepsis, which killed Murray, occurs when the body turns on itself while trying to fight off an infection. Eventually, blood pressure drops and organs suffer.

Proving a connection could be difficult, experts said.

“What may satisfy as a medical matter may be harder to prove to a jury in a legal sense,” said David A. Harris, a University of Pittsburgh law professor.

Filing charges, Harris said, would require prosecutors to show that Murray’s death was directly linked to the shooting.

“What were intervening circumstances? Lifestyle habits? Medical issues?” Harris said. “A lifetime, literally, has gone by.”

Legal experts said there is no prohibition against filing a homicide charge against Nicholas even though he was already convicted of lesser crimes.

Double jeopardy doesn’t apply, they said, because Nicholas was never charged with homicide in the first place.

Nicholas’s previous plea to aggravated assault is irrelevant, said Bruce Antkowiak, who teaches law at Saint Vincent College

“It’s a different charge based upon new facts,” Antkowiak said. “It may be the same incident, but it’s not the same crime.”

Still, Nicholas would be able to assert self-defense again.

Even if prosecutors think they can win the case, they must weigh whether they want to try.

“The DA may look at this and say it’s not worth it,” Antkowiak said.

Among their considerations: Do they still have the evidence? Are witnesses still alive to testify? What about the arresting officer and crime-scene technicians?

“Thirty-five years is an eternity, and they may not be able to prosecute this,” Antkowiak said.

Many of the police officers who investigated the shooting and were listed as witnesses during the trial have died.

While a prosecution decades later might be difficult, it’s not impossible. There is precedent in Allegheny County.

In 2007, Zappala’s office filed homicide charges against two men — Stevenson Rose and Shawn Sadik — when a woman they beat severely died from her injuries 14 years after the crime.

Both men had been convicted of aggravated assault and related counts in the case.

The victim, Mary Mitchell, was assaulted so badly in Larimer Park that she remained in a nursing home until her death from pneumonia.

At the time Mitchell died, Rose and Sadik were still serving their sentences for aggravated assault.

Both men had separate jury trials for criminal homicide in 2010. Rose was found guilty of third-degree murder, and Sadik was convicted of first-degree murder a few weeks later.

No moving on

After he left prison, Nicholas said, he resolved to lead a good life and help those he could.

He said he volunteered for years at a local hospital, coached Little League baseball, taught CPR classes and volunteered with Drum Corps International. He said he keeps emergency supplies in his car in case he comes across stranded motorists.

Nicholas vividly remembers the feeling of hugging his son goodbye the morning he turned himself in, and thinking that because of what he’d done, Murray would never have the same chance.

“That hurt me to my core,” Nicholas said.

He said he thinks about Murray daily, and he dissolves to tears when talking about what happened.

“I’ve never moved past that,” Nicholas said.

It’s clear that Murray’s father hasn’t either.

On the front porch of his home, two of his son’s wheelchairs rest folded up.

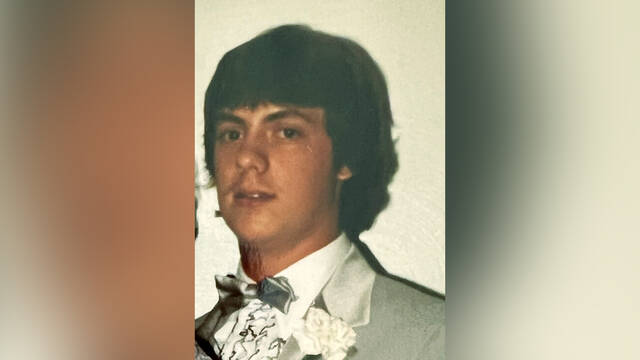

Sitting on an aluminum chair, the senior Murray thumbs through a manila folder with the original police report from the night of the shooting, medical records, photographs of his son — from before the shooting and after — and other important papers, like his son’s resume.

Before he was shot, Murray, a 1982 South Hills High School graduate, was looking for work as a draftsman.

Inside Murray’s house, two gray finches, Rossi and Murphy, chirp and tweet.

They belonged to his son. Now Murray cares for them in their large black cage.

“Hi guys,” he said to them last Monday, trying to prompt them to interact with a visitor.

Throughout a three-hour interview with TribLive, Murray often meandered. He talked about his life — the construction jobs he held, the work he did on his cars, collecting glass bottles.

But those stories seemed always to revert to anecdotes about his son — being on job sites together, helping him work on his car as a young man, going out together to dig for bottles.

All before he was shot.

“Why did a 31-year-old need to carry a gun?” Murray asked. “I miss my son.”